I love finding old things. I always have.

I’m not sure where this strange proclivity came from, but my earliest memories show it was embedded even then. Wandering through The Piggery - the abandoned pig farm and swampland behind my house in Topsfield, Massachusetts - was a never ending treasure hunt for me. I would spend hours unearthing seemingly-ancient tin cans and whiskey bottles, excavating the rotting walls of old buildings rapidly succumbing to the pull of moist earth, and sitting in the cab of a Studebaker E-series truck lodged deeply into the mud.

As a child - and still as an adult - my mind wanders when finding these things. The discarded flotsam of old, cast aside as unwanted, unneeded, unimportant, or a combination of all, they quickly become items of fascination to me, trash transformed to treasure, each object spilling forth stories - real or imagined - of the life it led and the experiences had by the last to handle it. Extracting the story from the found object - be it real and researched or a bit of historical fiction - feels like Dumbledore pulling memories from the pensieve, inextricably tying a bit of today with the fabric of yesterday.

A man who has once looked with the archaeological eye will never see quite normally. He will be wounded by what other men call trifles. It is possible to refine the sense of time until an old shoe in the bunch grass or a pile of nineteenth century beer bottles in an abandoned mining town tolls in one’s head like a hall clock.

- Loren Eiseley -

For those who know me, you know this love of history, of the who, what, where, and why that came before, has been a major part of my climbing and adventure career over the years. I’ve been fortunate to follow the footsteps of Shackleton, help excavate ancient tombs in Mustang, share the story of Everest 1963, and be a part of sharing the story of the pre-World War II climbs on Everest. These, for me, have been the most rewarding trips, climbs, and expeditions of my life - far better than reaching a summit - for they brought me in touch, often close, intimate touch, with those who came before, charted the path, created their present and informed our future.

One of my fondest moments of adventure trash picking was excavating the 1933 Camp VI at 27,400 feet in the Yellow Band on Mount Everest in 2001. I won’t go into detail about that day here, as you can read all about it in the link above. But, I came back to the ‘33 Camp again in 2003, and 2004, and for a final visit in 2019 to enable my friend, Sid Pattison, to sample the quasi-edible delicacies hidden within.

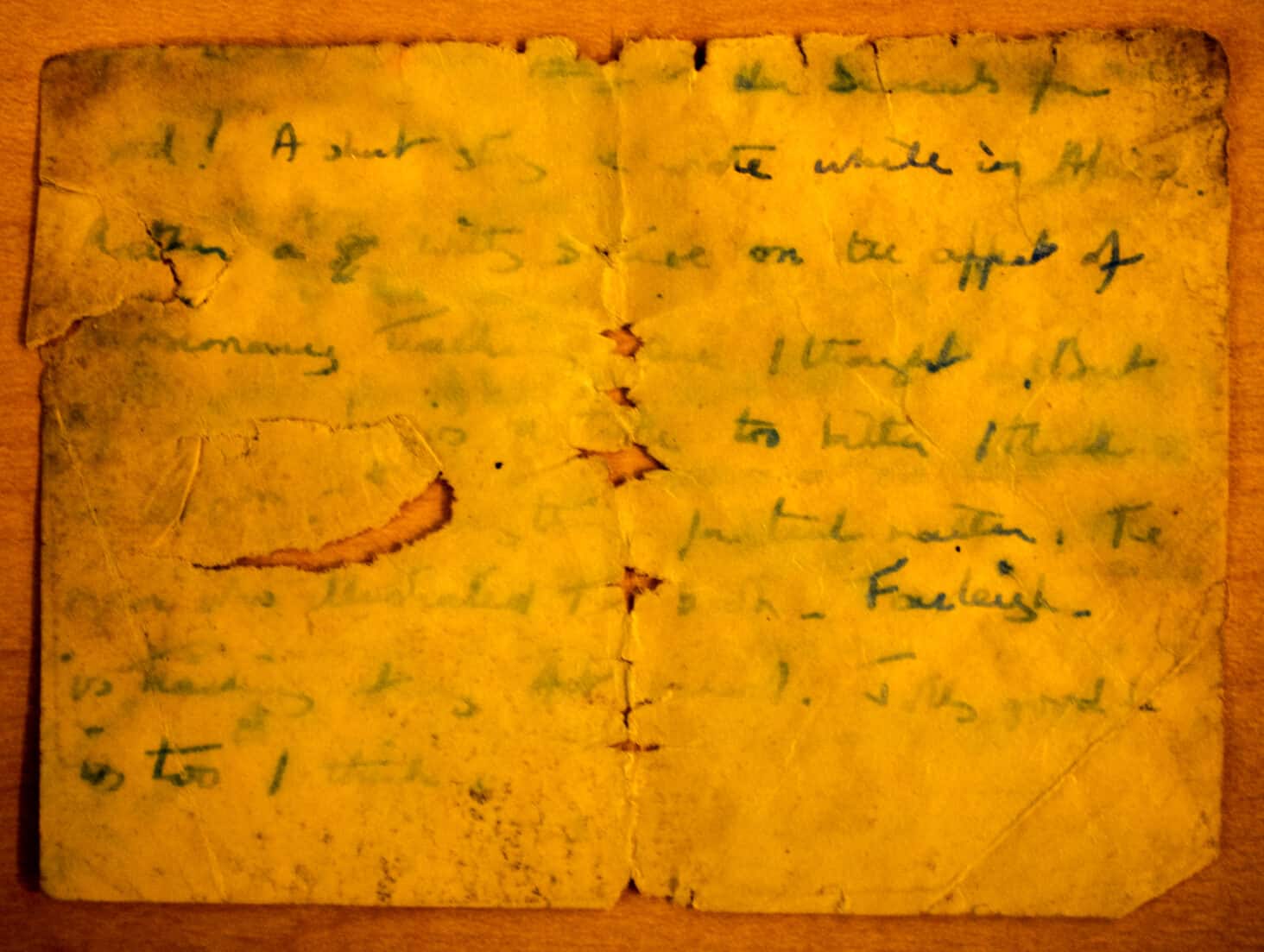

Amazingly, despite having looked through the camp multiple times, there was still something left behind. Looking at the tattered sleeping bag cemented with decades of ice to the canvas tent floor, my eye caught something sticking out. It was tiny, just a dab of yellow in a sea of earth tones, but enough to entice. Looking closer, I could see it was paper, and paper that had been written on. Windblown snow flying, I pulled and pried, used bare hands to melt the ice, and separate layers of fabric, eventually freeing the entire thing.

It was several sheets of paper, folded in half, frozen solid with the snows of 86 years (and sadly, grossly, the urine of climbers who stopped here for relief, oblivious to the history under their feet). I tucked it into a ziplock baggie with some silica packets to help dry it out, and we moved onward down the Longland Traverse. Immediately, the voices and images of the past came forth: Eric Shipton or Frank Smythe - the last two to occupy the camp - sitting in a squall, blowing on hands to warm them as they wrote - what - a journal entry? Notes about the climb? A letter to a loved one? Then, too cold to continue, neatly folding the papers up, tucking them beneath the sleeping bag for safe keeping, only to forget to retrieve them the next morning, words on paper abandoned with all else at a forlorn camp high in the Himalaya.

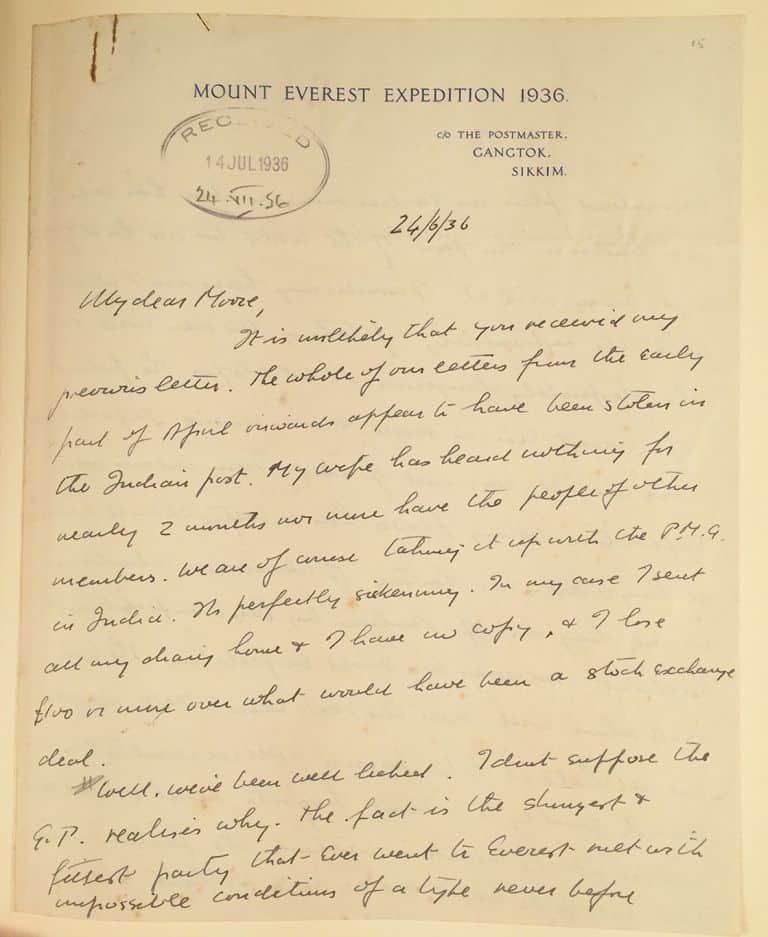

That evening, back at our Camp VI, I opened up the papers, delicately drying and separating the worn pages. To my dismay, the decades of abuse - storm and wind, sun and ice sublimation, climber’s crampons and boots and urine - had taken their toll, and much of the writing on the pages was rendered unreadable. Only snippets are clear, brief, fragmented glimpses into the thoughts percolating in 1933. But, there was just enough for me to compare the handwriting on these pages with that of Frank Smythe from letters auctioned off, and make (I think) a match.

See the original auction and other Smythe items here.

Frank Smythe. Wow. A legend of legends, a Himalayan hero taken too soon, a writer and thinker and climber bar none. To hold this letter - albeit unreadable - and know his hands were the last to touch it prior, scribbling thoughts and ideas and emotions and notations in the punishing cold of Camp VI…unfathomable.

At least to me. To some, understandably, just another bit of trash on Everest.

But to me, it will always be treasure, of the best and most meaningful kind.

How wonderful! The letter is quite beautiful in its way. And how is it you have a photo of the old Studebaker at the Piggery. Fascinating explorations - including eating artifacts!

Ha, yes, the old Studebaker...I took that when I was there with the kids rambling around back in 2013 or something. It's still there, but in rough shape as the swamp consumes it slowly!

Wonderful stuff Jake, I know exactly how you feel about these things.

Thanks, Dave - glad I'm not alone in all this!

Hi Jake, great piece about the 1933 camp finds. Hope you will write a book documenting your incredible searches and expeditions on Everest since the 1999 Mallory and Irvine trip. Hope you don't give up! I want you to be the one to find Irvine. Al

Thanks, Alan - much appreciated! I'll keep digging as much as I can. Still hopeful someday we'll know more! Be well, and thanks again!

Here’s something neat about that letter.

Those few words that are still legible on the first page read:

… a short story … wrote while in Africa. Rather a witty satire on the effect of missionary … I thought. But … too bitter I think… matter… who illustrated … Farleigh. Jolly good it is too I think.

So there’s a book being described, and given those clues it must surely be The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God, by George Bernard Shaw, written in South Africa in 1932 and printed in London the same year with illustrations by John Farleigh. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Adventures_of_the_Black_Girl_in_Her_Search_for_God .

Your mountaineer at 27,000 feet is writing (or more likely reading) a letter about a new short story by George Bernard Shaw.

Also, you could probably place a bet on the identity of the sender, on the basis of the listing for those Frank Smythe letters you link to. “The bulk of these letters are written to Smythe’s literary agent Leonard P. Moore (1876–1959) in England“ – and in the picture you include, Smythe’s talking about a previous letter that Moore has sent him, so Moore was obviously writing to him in the Himalayas during his expeditions. Moore sounds like a fascinating figure, a significant player on the 1930s publishing scene who was literary agent to George Orwell, most famously, but also to many others.

Obviously, many a slip and all that, and perhaps it’s some other correspondent of Smythe, or of Eric Shipton. But that appraising tone as they talk about new books, that interest in the illustrator… they do sound, now you come to think of it, rather like a literary agent. And if the writer is Moore, then while publishing archives have been retrieved from some weird places over the years, this would definitely be among the weirdest.

Hi Matt,

All I can say is...Wow! You are amazing! You not only deciphered a lot more of the letter's contents than my feeble brain was able to, but then put it together to - in my opinion - sort out not only what is being discussed, but who wrote the letter!

I just assumed the letter was written by one of the camp occupants - Wager, Wyn-Harris, Shipton, or Smythe - and for some reason didn't think it might have been a letter they were reading, not writing. And, seems spot on that it would be Moore and that Smythe would have been writing to him a lot during the '33 expedition, discussing books by others and potential books by him, as Smythe was feeling he needed to do more in the "serious business" of writing. Which he did, of course, writing some 27 books, all but 3 of which came out after the 1933 expedition.

Again, cannot thank you enough for shedding light on this letter and "mystery!" It does seem to qualify as a weird place to find a publishing archive!

Thanks again, Matt, and keep in touch!

Oh, and out of curiosity, how did you come upon this post?

Dear Jake,

My educated guess would be that machine learning (ML) techniques might be able to read the letter (especially now, once you have a sample of a good handwritten letter by Frank Smythe with known contents, and possibly in combination with spectroscopic techniques used by art-historians). Possibly guys from Carnegie Mellon uni would be able to help (they are arguably world's top in ML-related stuff).

(Meanwhile, tip off the Stetson to Matt too!)

Best,

Maxim