I didn’t recognize him. I probably should have, but honestly - embarrassingly - I did not.

Without doubt, I knew his face. And of course I knew his story, it being a seminal, foundational part of the climbing pantheon.

Perhaps I didn’t recognize him because he didn’t fit the bill, he was not the climber I expected him to be, larger than life, boisterous and perhaps a bit pompous, ready - eager even - to share with anyone who would listen his stories of bravery and courage. Instead, he stood quietly in a tweed coat, almost diminutive, chatting with those gathered at the American Alpine Club.

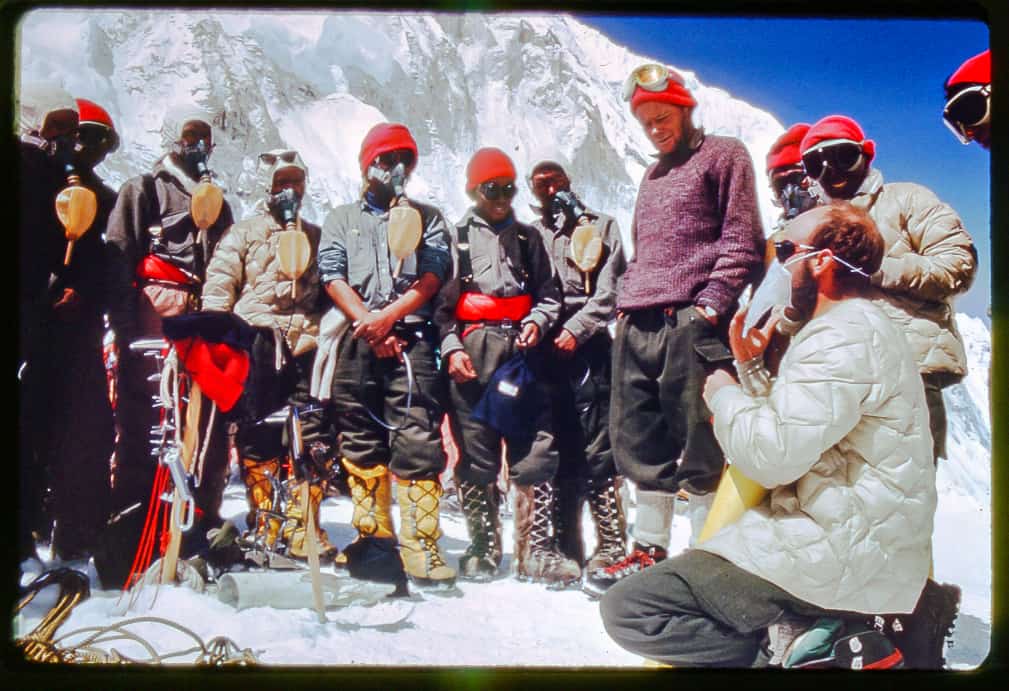

Photo by Barry Corbet.

When he was introduced to me, he stuck out his hand and said simply: “Hi, I’m Tom, great to meet you.” There was a flicker of recognition in the deep recesses of my brain, but not enough to parse it all. We chatted for a bit about mountains, about risk and philosophy and what we can learn from climbing - and how we can apply it to life. The flickers flickered a bit more - some hint that I knew this man - but still not enough. It wasn’t until I walked away after ten minutes, pulled into some other conversation, that it hit me.

“Holy shit, you idiot!” I thought, heart fluttering with angst. “That was Tom Hornbein! That was your childhood hero, and you didn’t even recognize him!”

I went back over once Tom was free again, and sheepishly apologized. Always gracious, and never seeking a pedestal, Tom smiled, eyes twinkling: “It’s ok, lad. I’m not like Big Jim [Whittaker] - I’m easily missed in a crowd.”

My relationship with Tom began in words, years before. In 1986, I had just come off my first climb, up Washington’s Mount Rainier. Afterward, my dad and I went to my great Uncle Roe Duke Watson’s house. Sensing I was trying to figure out this climbing thing, my twelve-year-old brain straining to understand it, Duke disappeared into his office, returning a moment later with a smile.

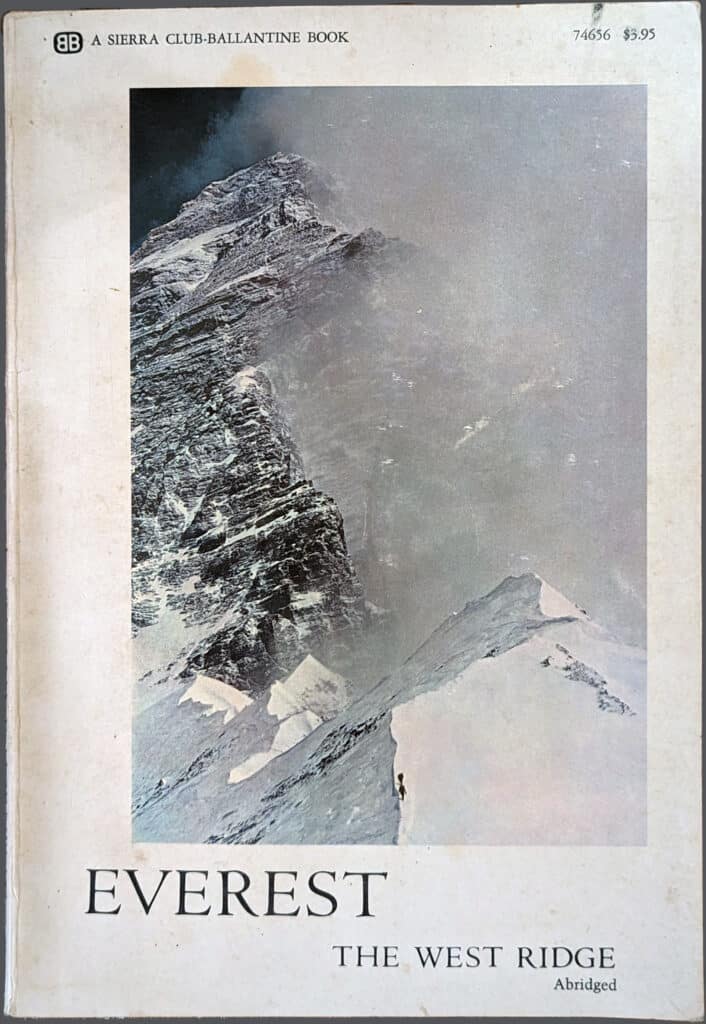

“Read this,” he insisted, handing over a well-worn book. “It’s by an old friend, and perhaps the best climbing book ever written.”

The cover captivated me immediately: two tiny figures picking their way up a whale-backed ridge, about to disappear into the vast immensity of a Himalayan peak.

I would soon learn those two figures were Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld embarking on their groundbreaking climb of Mount Everest’s West Ridge in 1963. I devoured the book, and it inspired that 12 year old kid to dive into climbing, into the mountains and their meaning and purpose beyond mere courage and conquest.

What I loved, and love, about Everest: The West Ridge (library) is precisely what I loved, and love, about Tom: his 1963 classic is not the egotistical, hubristic tome rife with chest-pounding and self-aggradizement so often found on climbing bookshelves. Rather, Tom’s book is one of philosophy and introspection, deep reflection on the nature of a climb and climbing, and even more a pondering about life, its meaning and its purpose, the interplay of risk and choices and responsibility, desire and drive and love and beauty.

I read and re-read Tom’s book many times over the years, digesting it’s meaning, trying to incorporate his philosophy into my own life and my own climbs. I never imagined I’d actually meet the man (and not realize I had), nor that we would eventually become friends.

After my gaffe at the AAC, Tom and I grew connected, serving together on the Board of the American Mountaineering Museum, working with others to select recipients for the Hall of Mountaineering Excellence award, and then working closely for over a year with David Morton and Jim Aikman on our 2013 film High and Hallowed: Everest 1963, which focused on Tom and Willi’s West Ridge climb.

Often, when we meet our heroes in life, we find them a bit less (sometimes a lot less) heroic in the flesh than in the press. In person, they rarely live up to the pedestalled, gilded, idealized, sanitized version we’re led to believe in, and seeing their inevitable and humanizing fallibilities - ego, uncertainty, anger, whatever - often elucidates a degree of disappointment.

Not so with Tom.

If possible, Tom in the flesh was even a better representation of the heroic, introspective Tom who narrates and philosophizes The West Ridge. In person, he lived out his ideas from 1963, ideas about life and its meaning, its purpose, about risk and reward, about the vagaries and unknowns of existence, about how to live life - with all its idiosyncrasies and imperfections - and embrace death. What to me made his book so exceptional - and made Tom the same - was his embrace of uncertainty, acceptance of imperfection, and drive to seek answers and new challenges throughout his life.

High and Hallowed: Everest 1963.

Early in the book, Tom wonders why he is even going to Everest in the first place:

Why was I here? I seemed to be hunting for answers to questions I couldn't even ask. What difference could Everest make even if I got to the top? What was up there to make me any wiser? Nothing but rocks and snow and sky.

- Tom Hornbein. Everest: The West Ridge

One of my first intimate meetings with Tom was back in 2009. I was pushing an expedition that year to make an attempt on the West Ridge as well as the Southeast Ridge. But, planning a meeting was difficult, as Tom had, at age 80, decided to learn piano, and was busy with his teacher most days. (I couldn’t help but ask myself what kind of person would take up piano at that age? I’d soon find it is the Tom Hornbein type of person who does that.) We eventually found a time, enjoyed a hearty lunch at his home beneath Lumpy Ridge with his wife, Kathy, before heading out on a scrambly hike.

Despite arthritis, Tom moved deftly, clambering up rocks and over ridges, all the while telling stories of his early, foundational days in these same mountains. He spoke of life - his life - and the failures and stumbles and challenges he’d faced. After two hours, we’d barely touched on the West Ridge specifically, but in hindsight I realized we talked about it the entire time - its symbolism in the fabric and structure of Tom’s life, of all our lives.

Still I marvel at the relative ease with which I decided to bypass a much greater guarantee of success for a bit more challenge and gamble, a bit more opportunity for failure-and therefore fore a lot more feeling of accomplishment should we pull it off.

- Tom Hornbein. Everest: The West Ridge

I last spent time with Tom nearly a year ago. Tom and Kathy kindly asked me to come to their home a bit early so Tom and I could catch up before others arrived for dinner, conversation, and a screening of Jim Aikman and Connie Self’s film Metanoia about the life of Jeff Lowe.

Tom and I sat in the sunroom discussing life…and its corollary, death. My mother was sick at the time with cancer, so life, death, and what to make of it all was much on my mind. Tom, after battles with sepsis and the challenges wrought by age, had been grappling with the same. We talked about Oliver Sacks and Alan Lightman, philosophy and religion and their takes on the beginning, the end, and all that comes between. We talked about Barry Corbet, Tom’s friend and hero, and John Evans, and the now dead members from 1963: Willi Unsoeld, Jake Brietenbach, Ngawang Gombu, Dick Emerson, Barry Bishop, Lute Jerstad, Dick Pownall, Dave Dingman, Norman Dyhrenfurth, Al Auten, Will Siri, Jimmy Roberts, and more.

Tom talked about how he’d had a full life, a charmed life, with no complaints. He was grateful for his hard work and success, and acknowledged his many mistakes and imperfections. He spoke of his family, eyes misting noticeably, seeing their faces in his mind’s eye, choking back understandable tears. And then, recomposing, he said with utter sincerity: “Like your Mom, I can’t say I’m excited about death. I’ll miss things. I’ll miss the spice of life, the wonder of tomorrow. But, I’m not afraid of death, either. It’s part of it, part of life, and I’ll welcome it when it comes.”

Suppose we fail? The thought brought no remorse, no fear. Once entertained, it hardly seemed even interesting. What now mattered most was right here: Willi and I, tied together on a rope, and the mountain, its summit not inaccessibly far above. The reason we had come was within our grasp. We belonged to the mountain and it to us. There was anxiety, to be sure, but it was all but lost in a feeling of calm, of pleasure at the joy of climbing. That we couldn't go down only made easier that which we really wanted to do. That we might not get there was scarcely conceivable.

- Tom Hornbein. Everest: The West Ridge

Last week I received the sad news that Tom had entered hospice, had begun his final climb and last earthly adventure. I was heartbroken. The world would soon be significantly dimmer. I hadn’t made it up for one more visit as I had promised myself I would. I kept telling myself that someone like Tom - someone who had survived the epic of the West Ridge - couldn’t possibly die, would never come to the end of the proverbial rope. But of course I knew that was nonsense: Tom, like all of us, would someday pass. We all will; we all have a limited number of days with which to work, to impact our lives and our world and all those around us. Tom knew it, and spoke of it every time we were together.

We felt the lonely beauty of the evening, the immense roaring silence of the wind, the tenuousness of our tie to all below. There was a hint of fear, not for our lives, but of a vast unknown which pressed in upon us. A fleeting feeling of disappointment- that after all those dreams and questions this was only a mountain top-gave way to the suspicion that maybe there was something more, something beyond the three-dimensional form of the moment. If only it could be perceived.

- Tom Hornbein. Everest: The West Ridge

And thus, he lived life, lived it fully, completely, robustly, whether it was in the hospital or the classroom, in a boardroom or a living room, with his friends and family or those he scarcely knew, or on the slopes of Everest. Tom embraced risk - the all-important risk of grasping and savoring the zest of this existence - and in so doing, he taught me and myriad others and became, unwillingly and unwittingly, a hero.

The final paragraphs of The West Ridge are, to me, a wonderful summation of the wisdom and wonder Tom brought to his climb, to his book, to his life, and to mine:

Existence on a mountain is simple. Seldom in life does it come any simpler: survival, plus the striving toward a summit. The goal is solidly, three-dimensionally there-you you can see it, touch it, stand upon it-the way to reach it well defined, the energy of all directed toward its achievementment. It is this simplicity that strips the veneer off civilization and makes that which is meaningful easier to come by-the the pleasure of deep companionship, moments of uninhibited inhibited humour, the tasting of hardship, sorrow, beauty, joy. But it is this very simplicity that may prevent finding answers to the questions I had asked as we approached the mountain.

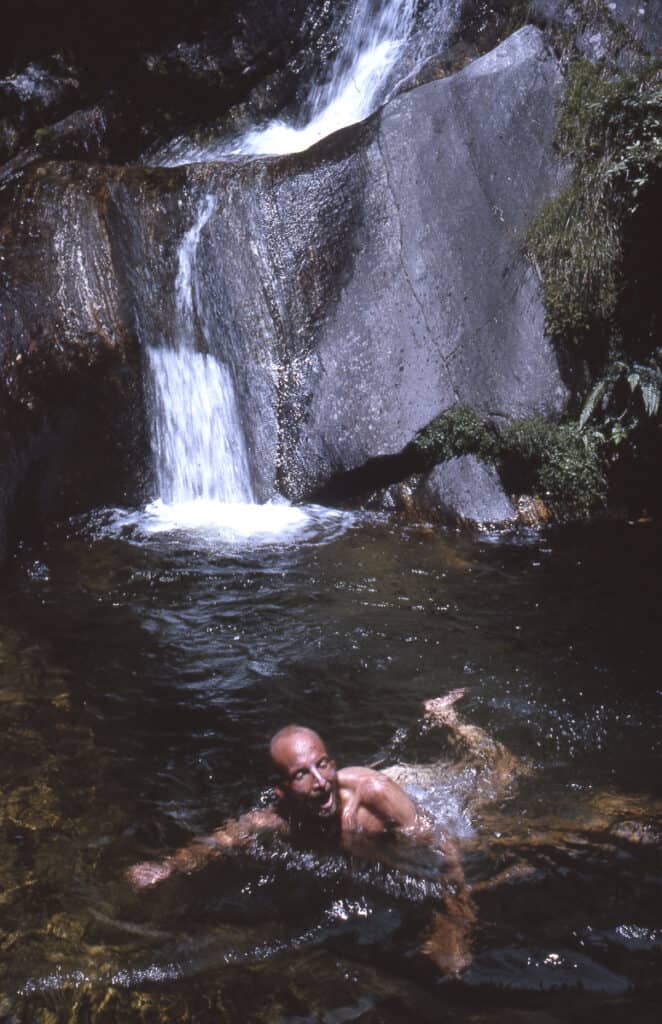

Then I had been unsure that I could survive and function in a world so foreign to my normal existence. Now I felt at home here, no longer overly afraid. Each step toward Kathmandu carried me back toward the known, yet toward many things terribly unknown, toward goals unclear, to be reached by paths undefined.

Beneath fatigue lurked the suspicion that the answers I sought were not to be found on a mountain. What possible difference could climbing Everest make? Certainly the mountain hadn't been changed. Even now wind and falling snow would have obliterated most signs of our having been there. Was I any greater for having stood on the highest place on earth? Within the wasted figure that stumbled weary and fearful back toward home there was no question about the answer to that one.

It had been a wonderful dream, but now all that lingered was the memory. The dream was ended.

Everest must join the realities of my existence, commonplace place and otherwise. The goal, unattainable, had been attained. Or had it? The questions, many of them, remained. And the answers? It is strange how when a dream is fulfilled there is little left but doubt.

- Tom Hornbein. Everest: The West Ridge

Rest in peace, Tom Hornbein. You will be missed, but your spirit remains.

WELL WRITTEN ....................

ONE WOULD NOT EXPECT LESS>>>>>>>>>>>>

Thanks, Babu!

Awesome memorial. My condolences to you, having been his friend.

Take risks, carefully.

Live and love by what you learn from testing yourself.

Thank you, Al, and well said!

Thanks Jake. That final quote by Tom is pretty deep and makes my head spin once again. What goal did he attain or not attain? Why was he there at all? Was he more at home on the terrifying mtn or back in the real world that he found terrifying? Lots of questions and much deeper than just climbing a mountain.

Thanks Alex

Thank you, Alex. Yes, that final quote - and ending to the book - has always captivated me, as it's so contrary to so much of mountaineering literature with it's deep questioning, supplying few answers, pondering, no simple solutions or answers. For me, it is far closer to the true nature of mountains and mountaineering than most of the other works out there. Thanks again, and hope you are well!