I can’t see myself coming down defeated.

- George Mallory to his wife, Ruth, 1924 -

Each spring, the news reports inevitably flow in: horrendously long queues high on Mount Everest, nose-to-butt climbers waddling toward the summit, an unnaturally, irrationally high number of them bound to die not from falls, not from storms, not from “normal” climbing accidents, but from an obsession with the top, with the summit, with that little patch of snow covered in trash and urine and footprints. With, to put it simply, a distorted barometer of success, one that places meaning only on the top, and relegates the journey, the process, the adventure - and perhaps the failure - to the backseat.

I’ve written and reflected on this before, but in today’s Thursday Thought I wanted to delve a bit into the earliest history of this summit obsession and how its dangers have been in plain sight for a century.

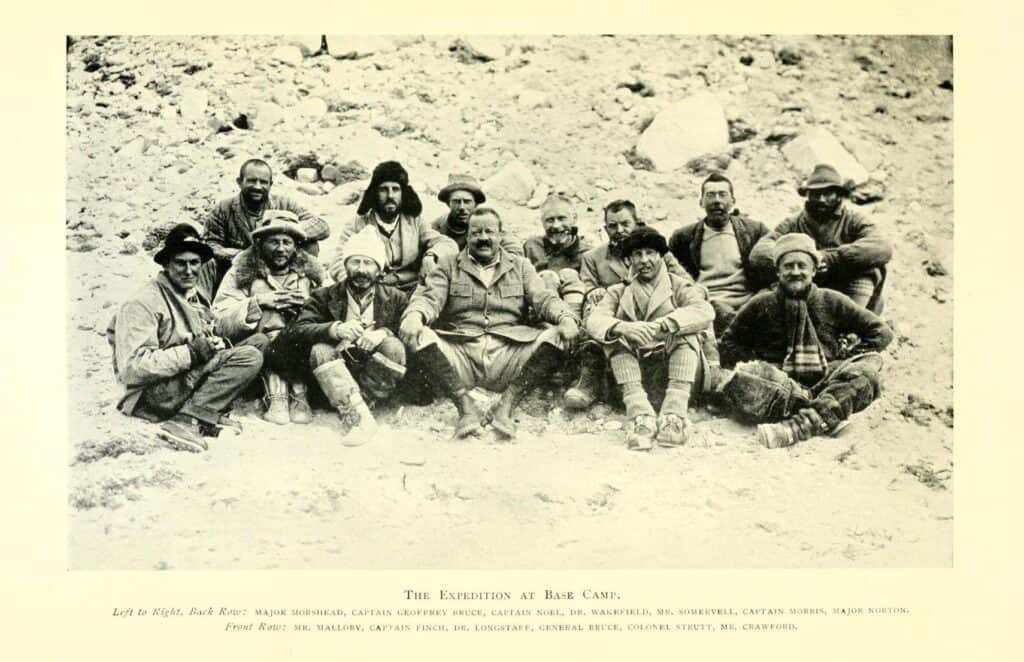

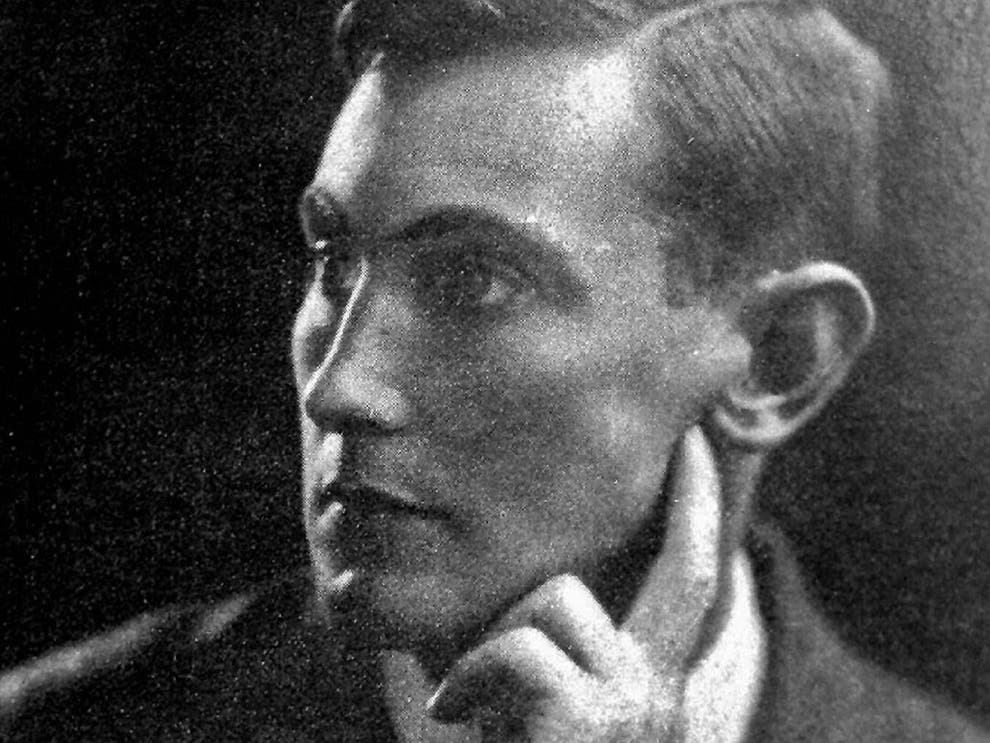

Well documented, researched, and discussed is the famous, tragic disappearance of George Mallory and Andrew Irvine on June 8, 1924, somewhere near the summit of Everest. Whether or not they reached the top remains a stubborn mystery, and that question has understandably overshadowed nearly all other discussions of the ‘24 expedition and its outcomes.

Of particular note - and fairly lost outside of climbing circles - is the summit attempt that happened just before Mallory and Irvine’s disappearance. It was June 4, 1924, when two climbers - Teddy Norton and Howard Somervell - moved slowly across the mighty North Face of Everest. They were aiming for the Great (now Norton) Couloir, avoiding the severe obstacles on the Northeast Ridge like the Second Step, and hoping to reach the top by traversing onto the north side of the summit pyramid.

Oh, and they were climbing without bottled oxygen. In tweed coats and woolen knickers.

Somervell, fatigued from months on the mountain and with labored breathing from a frostbitten larynx, stopped somewhat shy of 28,000 feet and waited while Norton continued, unroped and alone, into the Couloir. Norton moved forward across daunting, downward-sloping tiles of rock covered in fresh, unconsolidated snow that obscured everything, with a 7,000 foot drop to the Central Rongbuk below. At 28,126 feet, moving through at-times-waist-deep snow, with less than 200 vertical feet to go before the terrain noticably eased off, Norton called it a day. In his words:

It was not exactly difficult going, but it was a dangerous place for a single unroped climber, as one slip would have sent me in all probability to the bottom of the mountain. The strain of climbing so carefully was beginning to tell and I was getting exhausted…I had perhaps 200 feet more of this nasty going to surmount before I emerged on to the north face of the final pyramid and, I believe, safety and an easy route to the summit. It was now 1 p.m., and a brief calculation showed that I had no chance of climbing the remaining 800 or 900 feet if I was to return in safety…

I feel that I ought to record the bitter feeling of disappointment which I should have experienced on having to acknowledge defeat with the summit so close; yet I cannot conscientiously say that I felt it much at the time. Twice now I have had thus to turn back on a favourable day when success had appeared possible, yet on neither occasion did I feel the sensations appropriate to the moment. This I think is a psychological effect of great altitudes; the better qualities of ambition and will to conquer seem dulled to nothing, and one turns downhill with but little feelings other than relief that the strain and effort of climbing are finished.

- Col. E.F. “Teddy” Norton, The Fight for Everest 1924, page 113 (free on archive.org)

In his description, Norton attributes much of his decision to a combination of understanding the realities of the situation and the lassitudinous nature of extreme altitude. Having experienced both personally, I don’t disagree…But, I think there is another element at play.

Going into the expedition in 1924, Norton was a decorated officer and had been made Lieutenant-Colonel. He had chosen the army as his career, and would stay at it for 40 years, eventually attaining the rank of Lieutenant-General. Similarly, Somervell was a trained surgeon, decorated in the horrors of World War I medicine, and having seen the poverty and need in India after the 1922 Everest expedition, he dedicated the rest of his life to medical work in the subcontinent.

In short, both Norton and Somervell had careers about which they were passionate and dedicated. They were strong and gifted climbers, true mountaineers by any measure, and gave all they had to the expeditions of ‘22 and ‘24. But, they were not fixated on the summit; they were not looking for Everest - and its summit - to transform their lives in any meaningful, structural way. They were there for the journey, the adventure, the challenge, and to return home better for it.

Back at Basecamp after their attempt, Somervell wrote:

There is nothing to complain of. We established camps; our porters played up well; we obtained sleep even at the highest altitude, nearly 27,000 feet, and we had gorgeous days for the climb, almost windless and brilliantly fine, yet we were unable to get to the summit. So we have no excuse. We have been beaten in a fair fight - but the fight was worth it every time, and we shall cherish the privilege of defeat by the world's greatest mountain.

- Howard Somervell from The New York Times, quoted in The Nation, July 9, 1924

Their teammate and friend, George Mallory, had - I firmly believe - a very different perspective about the expedition and motivation for reaching the summit, and one that most likely got him and Andrew Irvine into trouble on that fateful day of June 8, 1924.

Mallory was a gifted man in all regards: handsome, intelligent, witty, engaging, and a remarkable climber. His friend and mentor, Geoffrey Winthrop Young, called him Galahad of the mountains, and watching him move on steep terrain was said to be like watching poetry in motion. Mallory went to Cambridge, was close with the Bloomsbury Group, and had lofty life aims of international work, writing, artistry. In 1921 and ‘22, he was a teacher at Charterhouse School, and in 1924 was granted leave from his position as lecturer at Cambridge to return to Everest. Mallory was also married to the love of his life, Ruth Turner, and together they had three children: Clare, Beridge, and John.

But, despite his myriad gifts, one can’t help but believe Mallory went to Everest - not once, but three times - for something more than just adventure, more than just climbing, more than just the challenge of the peak. He was looking for Everest to change him, transform him from a gifted man lecturing and teaching into a household name, a conqueror of the highest mountain on earth, savior of the spirit and soul of the crumbling British Empire. He was looking, hoping, yearning that his time on Everest would change his course, set him up socially, financially, so that he could be with his wife and his children comfortably, and not have to return to Everest again.

The problem? The only way for Mallory to do all of that was to reach the top, stand on the summit. And, for him, this quest - this specific outcome - became his barometer of success, and the summit became his singular focus.

In 1921, on the first expedition, Mallory wrote to Ruth with palpable enchantment: “My darling, this is a thrilling business altogether. I can't tell you how it possesses me, and what a prospect it is.” Toward the very end of that expedition, as the weather hammered and the team was near exhaustion, Mallory pushed his weary teammates to make one last try at figuring out the route and, despite horrific winds and extreme cold, he made it to the North Col along with Bullock, Morshead, Wheeler, and three Sherpa climbers, unlocking the secret to the climbing route and thereby opening the door to “anyone who cares to try the highest adventure.”

Mallory swore he would not return to Everest after 1921, but in 1922 he was again trekking across the plains of Tibet en route to the mountain. They did remarkable things on the mountain in ‘22, not least of which was Mallory, Norton, and Somervell on May 22 setting a world altitude record of 26,985 feet (8225 meters) on the North Ridge, climbing without oxygen. Five days later, on the 27th, Geoffrey Bruce and George Ingle Finch broke that record, climbing to 27,316 feet (8326 meters) on the North Face, using bottled oxygen.

But, this was not enough for Mallory. He wrote of that first attempt - and record - in The Assault on Mount Everest, 1922:

And if we were not to reach the summit! None of us, I believe, cared much about any lower objective. We were not greatly interested then in the exact number of feet by which we should beat a record.

- George Leigh Mallory, The Assault on Mount Everest, 1922 (free via Gutenberg here)

The team retreated to Basecamp and, despite everyone being exhausted and the weather beginning to noticeably change to the monsoon, Mallory pushed for a third and final attempt. He wrote to Ruth on June 1 about wanting to try again, admitting that his frostbitten finger from the first attempt could get worse:

…and I risk getting a worse frostbite by going up again, but the game is worth a finger & I shall take every conceivable care of both fingers & toes. Once bit twice shy!

- George Leigh Mallory, letter to Ruth, June 1, 1922, from Fallen Giants (Archive.org)

On June 7, Mallory, Somervell, and Colin Crawford led a group of fourteen porters up the steep, imposing North Col headwall. Roughly two-thirds up the headwall, a large avalanche was triggered, knocking the British climbers off their feet and sweeping the three rope teams of porters down the face. Nine were pushed into a crevasse and buried. Two were eventually dug out and lived, while the remaining seven porters lost their lives - the first ever climbing deaths on the mountain.

Mallory was devastated, and rightly so, for the deaths came under his watch, a result of his ambition. To Ruth he wrote:

The consequences of my mistake are so terrible; it seems almost impossible to believe that it has happened for ever and that I can do nothing to make good. There is no obligation I have so much wanted to honor as that of taking care of those men.

- George Leigh Mallory, letter to Ruth, June 2,1922

Equally, he reflected on his own mortality, and what his death would mean to her, and to their three children:

It was a wonderful escape for me & we may indeed be thankful for that together. Dear love when I think what your grief would have been I humbly thank God. I am alive…

- George Leigh Mallory, letter to Ruth, June 2,1922

But, the sadness, the grief, the worry and acknowledgement of risk were short lived. As Robert MacFarlane notes in Mountains of the Mind:

…[T]he further Mallory gets from the murderous mountain, the more he falls back in love with it. By Darjeeling, the subject of the dead Sherpas has disappeared from his letters. His thoughts are only with Ruth. With Ruth, and with the possibility of the next trip.

- Robert MacFarlane, Mountains of the Mind (library)

Mallory of course returned to Everest in 1924 for his third and - he hoped - his final expedition. For him it was not a simple choice, leaving his wife and children for another long and dangerous expedition, but it was a choice he finally made in the affirmative. There was, though, perhaps a bit of premonition about the expedition. Shortly before departure, Mallory went with Geoffrey Winthrop Young to visit Kathleen Scott, widow of Robert Falcon Scott of tragic Antarctic fame. Soon after, he wrote to his friend Geoffrey Keynes of the upcoming trip: This is going to be more like war than mountaineering. I don’t expect to come back.

Despite the foreboding emotion, Mallory was soon on the ship to Bombay and Everest, his fears transitioned to excitement, even a touch of certainty about the eventual outcome. To his (maybe more than) friend Marjorie Holmes he wrote:

I must tell you my big news first: – I'm to go once more to old Everest…My chief feeling is: – we've got to win the top next time or never. We must get there & we shall. Here pause while I imagine my self getting to the top...

- George Leigh Mallory letter to Marjorie Holmes, 1924, from Bonhams auction

Not long after, after a strategy meeting on the Tibetan Plateau, Mallory wrote to Ruth about the devised plans: It is almost unthinkable with this plan that I shan't get to the top. I can't see myself coming down defeated. And, later to Tom Longstaff:

We are going to sail to the top this time and God with us — or stamp to the top with our teeth in the wind.

- Tom Longstaff, quoted in Time Magazine

And so Mallory arrived on the mountain that fateful spring, focused less on the adventure, the journey, the process, the artistry of the attempt ahead, and more than ever on that lofty patch of snow that had become the overwhelming propellant of his life. And, Andrew Irvine - who was less experienced but arguably equally motivated - was pulled into the maelstrom.

While we still don’t know - and perhaps never will - what exactly transpired in those final, fateful days and hours high on Everest, one thing is certain: Mallory and Irvine faced calamity, and it claimed them both. The few facts we do know seem to point to a long day high on the mountain, a day that took Mallory and Irvine toward the summit - maybe reaching it, maybe not - and found them still descending after sunset, or at the least late in the day…too late for safety, too late for prudence, too late for any margin of error.

In his quest for, desire for, need for the summit, it seems Mallory - and by association, Irvine, too - broke a cardinal rule of mountaineering: always leave time for a safe descent. And for it, they paid the ultimate price.

In The Epic of Mount Everest, Younghusband put it well:

[Mallory] knew the dangers before him and was prepared to meet them. But he was a man of wisdom and imagination as well as daring. He could see all that success meant. Everest was the embodiment of the physical forces of the world. Against it he had to pit the spirit of man, He could see the joy in the faces of his comrades if he succeeded. He could imagine the thrill his success would cause among all fellow mountaineers, the credit it would bring to England, the interest all over the world, the name it would bring him, the enduring satisfaction to himself that he had made his life worth while. All this must have been in his mind. He had known the sheer exhilaration of the struggle in his minor climbs among the Alps. And now on mighty Everest exhilaration would be turned into exaltation - not at the time, perhaps, but later on assuredly. Perhaps he never exactly formulated it, yet in his mind must have been present the idea of “all or nothing.” Of the two alternatives, to turn back a third time, or to die, the latter was for Mallory probably the easier. The agony of the first would be more than he as a man, as a mountaineer, and as an arust, could endure.

- Sir Francis Younghusband, The Epic of Mount Everest, pages 276-277

A tragic ending to an amazing life, and what could have - should have - been an early, foundational warning against the song of the summit sirens: the top never is - never was and never will be - worth one’s life. Success is not buried in the summit snows, heroism not hidden in the highest point, fame and fortune not worth finger or foot, or life.

Sadly, it was Ruth who ended up holding the bag, a 32 year old, widowed mother of three children suddenly alone, the love of her life vanished in the mist.

I know George did not mean to be killed…It is his life that I loved and love…Whether he got to the top of the mountain or did not, whether he lived or died, makes no difference to my admiration of him.

- Ruth Turner Mallory, letter to Geoffrey Winthrop Young

As we roll into yet another Everest season, as countless climbers are pulled forward, upward, to that high patch of snow, may they remember the story of 1924, resist the summit fever, and return again to the life their loved ones love.

What a great post Jake and so relevant for today’s Everest climbers - congratulations 👏👏

Thanks, Sujoy - much appreciated! I hope you are well, my friend!

Yes thanks a lot 😊😊

Anyone can be guilty of going for the win at all cost and losing one’s sense of objectivity and responsibility, but the collateral effects can be hard to see when you have the blinkers on. In Mallory’s case, he could be described as brave, heroic and selfless in the pursuit of the summit. Alternatively he could be described as selfish, reckless and having little regard for the welfare of his companions (the Sherpa in 22 and Irvine in 24) and the grieving family he left behind. Robert Scott faced similar criticism in his failed attempt on the South Pole – a reckless but heroic failure whose mistakes cost the lives of his men. It can be a fine margin between being a hero/villain, success/ failure, fame/obscurity – one bad decision or one slip. If Mallory hadn’t taken a fall he most likely would have returned home a national hero, but one slip and its all over. I suppose the reverse could be said for Hillary and Tenzing – one fatal slip or equipment failure and no one would know much about them. Having said that, I agree that Mallory seemed to lack judgement when taking risks and probably should have conceded defeat to save his own life and Irvines - of course we can judge with the benefit of hindsight to say its wasn’t worth the risk, but if Mallory had made it then it would all have been “worth it”.

Hi Alex, Thanks for your comment and - as always - great and solid insights.

I completely agree: the line between hero and reckless is a vague one, and often defined by whether or not one comes back from an "adventure" or not. And, I think you're spot on that had Mallory & Irvine returned from the mountain - regardless of how reckless or ill-advised their summit push may have been - they would have been heralded as heroes. Years back, I talked with members of the '63 American Everest expedition about Hornbein and Unsoeld's amazing ascent of the West Ridge. All of them - Hornbein included - noted in one way or other that had their attempt ended in tragedy, the "heroism" and "bold vision" of Tom and Willi would have been widely castigated as dangerous, reckless, irresponsible.

As for Mallory, I think his was a mixture of the two: He was smart, strong, able, confident, and often made good decisions. But, he was also motivated beyond perhaps his own powers of reasoning, the siren song of the summit calling him and dulling the pleading of his other half to be conservative, etc. In Ruth's words, I truly doubt Mallory meant in any way to die, or even thought of it as a real possibility (any more than any of us do on the high peaks), but was so motivated by, captivated and possessed by, the summit - and all the promise it held for him and his family - that he could not resist pushing further, higher, later into the day, "knowing" full well that it would all be ok...until, of course, it wasn't. I think that same pull hits many on the mountain these days.

Anyway, thanks for the thoughts, Alex, and be well my friend!

Thanks Jake. As you describe, the 63 climb seems extraordinarily bold/risky, with no escape plan but it paid off in a huge way.

I noticed you did a film a while back about the west ridge but were prevented from summitting. Seems like a wise choice.

Sadly Unsoeld died in 79 whilst on a seemingly routine descent with some kids. Sometimes its just terrible misfortune rather than reckless behaviour that gets you.

The aussie climb in 84 was also bold in the extreme but seemingly well managed and led. The youtube video is amazing. The other site raves about it quite often.

Thanks, Alex. Indeed, the 1963 West Ridge climb was incredibly bold, and it really ushered in a new era of Himalayan mountaineering, one in which climbers deliberately select the toughest route they can reasonably (or unreasonably) attempt/climb, rather than the easiest one, which had been the predominant choice until '63, especially on the 8000ers. I think it earned its iconic status as a climb of vision and heroism because Tom and Willi pulled it off; had they not, we'd likely have a very different interpretation of their climb. But, I guess that's the common narrative of so much of mountaineering and pushing the boundaries!

As for Willi, yeah, he died in an avalanche with students from Evergreen State College in February 1979 while descending Cadaver Gap on Rainier. You can read a pretty solid write up on the accident in the American Alpine Journal from 1980 here. While the conclusion at the time was that Willi, as expedition leader, made sound decisions, off the record I have heard a lot of gentle criticism of the decisions made, and a recognition that Willi made significant errors in judgment on that trip, and especially the final day. He was an amazing man, and it's well worth reading about him. Incredible in so many ways. But, he was an evangelist for risk taking in life, and perhaps to a fault, as it certainly played a big role in the tragic death of his daughter, Nanda Devi, on her namesake mountain in 1976 (see Nanda Devi: The Tragic Expedition by John Roskelly, and likely had something to do with his and Janie Diepenbrock's death three years later on Rainier. Tough stuff, for sure.

And, agree on Macartney-Snape's '84 climb. Amazing all around. But, also hanging it out there...and getting away with it. Had things ended up differently, I wonder what the climbing community's narrative would be about climbing the Norton Couloir in telemark boots without oxygen? Nonetheless, such a visionary, impressive climb! And, I, too, love the film!

I cannot imagine the physical and emotional strain of climbing the couloir with the wrong boots and no oxygen. Summitting at night as well. Too much for me.

Dear Jake, I've just found this site through the GMAS, which I recently joined. Although I've lived in Indonesia for the past 40 years, I'm from Birkenhead, and have a hometown interest in the two heroes. I'm no mountaineer, although I love mountain walking and have travelled a bit. I've got the Mayor of Wirral, (the area of Merseyside which includes Birkenhead), a reporter on the "Birkenhead News", the Williamson Art Gallery, which is just up the road from Mallory's house, and the Corwen Museum in North Wales where the Irvine family had a home, all interested. We owe it to the two brave souls to commemorate and honour them in an Exhibition for the Centenary next year. That's all for now, except to say I'm delighted to have found this site. "Adventure On" (John Masefield). Dachlan

Dear Dachlan,

Thanks much for your comment, and so glad you found my site! And, wonderful to hear from you with such a connection to Mallory and Irvine. I agree 100% that next year demands a full commemoration of their climb and the 1924 expedition as a whole. While much of it is superficially known to a great many people, the real meat of the expedition - what an undertaking it was, how remarkable the characters were, how much was accomplished despite not actually reaching the summit - is generally lost in the shuffle. It would be brilliant to see something big done to tell their stories to a bigger, wider audience. If I can ever be of service in that regard, please let me know!

Thank you again, and my very best,

Jake