On a rounded hilltop, lightly wooded, just off the corner of Bascom and Adair Roads northwest of Jackson, Tennessee, I squished my way through soggy leaves and mud, staring at graves and thinking about fences. The rain drove hard, sloughing down in great sheets of wet, making everything harder, darker, more intensely felt and viscerally experienced. There was no real fence around this place, just some tattered split rail delineating this one-acre plot deeded by Harriet McClellan for a family cemetery in 1884. But, inside, near the top of the rise, nestled amongst towering oaks, was a more precise, more defined fence that spoke volumes.

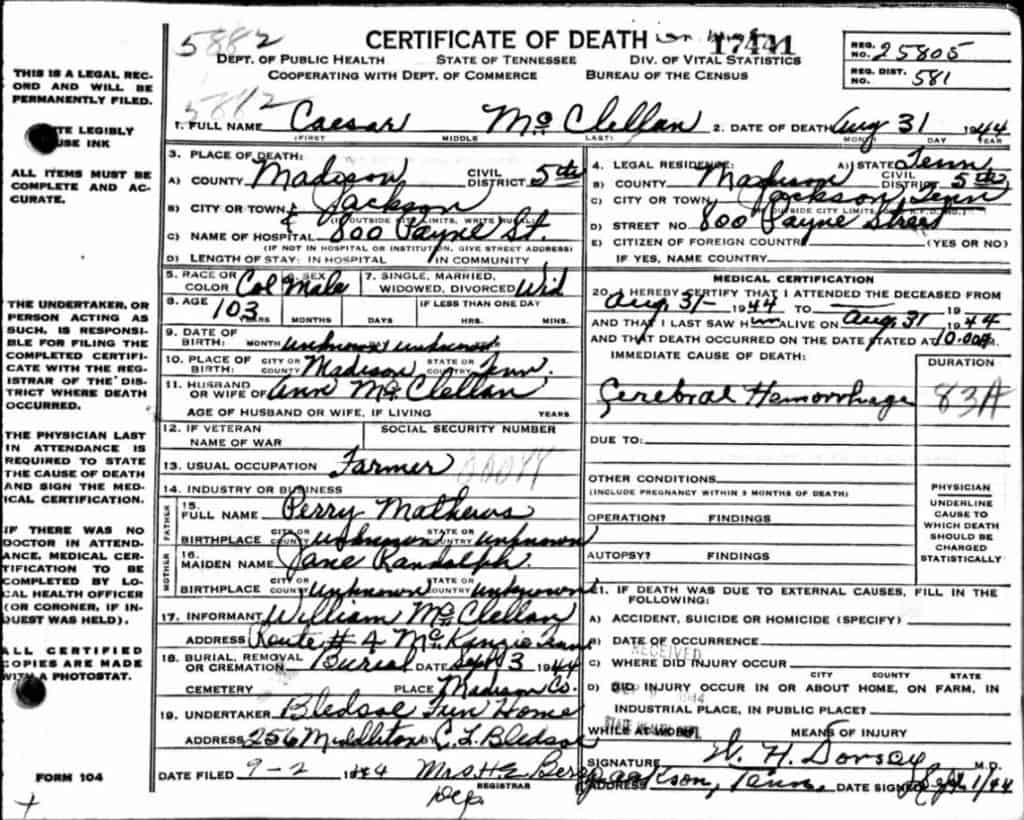

I was here looking for clues…clues that would offer some insight into the McClellan family of the antebellum period and the decades after the Civil War. My godmother, Helen Rhea, grew up partly in Jackson, and her great-grandfather, Caesar McClellan (1840-1944), was a part of this family, albeit an unwilling part. He might have been buried here - the records are hazy - and I was hoping to find his tombstone and any ancestral light it might provide.

To my right was the short-but-imposing wrought iron fence, a handful of tombstones within its protective guards: That wasn’t the place, although it was of interest. Rather, my goal was outside the fence, amongst the tumbled and broken gravestones, the ones inscribed with only a few words, some with just initials, some with nothing at all. These were the graves, the final resting places, of the people who toiled lifetimes for those lying peacefully inside the fence. This was the resting place for those enslaved by; owned by; likely beaten, degraded, tortured, and raped by the dead inside the fence.

Fences. How we love a fence in this country. I encounter them everywhere in the mountains of Colorado, from rusted barbed wire tacked on a tree to high spiked fences with electric gates. Big or small, grand or simple, they all convey one simple message: this is mine - that is yours; stay on the correct side, or else. Many of our fences are physical, like the one in the McClellan Cemetery, clearly defining the line between White and Black, have and have-not, privilege and poverty. Many more of our fences are hidden, lines of demarcation invisible to the naked eye, but nonetheless solid and effective in keeping some in and others out.

This disheveled cemetery was neglected, awash with leaves and weeds, fallen branches and broken tombstones, its forgotten status not dissimilar to the backwater of our national memory. Caesar’s grave was nowhere to be found, but his brother, Reverend John McClellan, was there, as were other relatives and many unknowns, their stories all but lost in the arc of history and convenient omission. But, the fence spoke volumes: its path through the trees, through the tombstones, was like the path through our history of stark division and disunity and inequality, of structural barriers - seen and unseen - keeping some in and others out.

Caesar was owned by the McClellans for the first 25 years of his life. Owned. Property. No more rights or entitlements than a couch or a horse. Our brutal and bloody Civil War granted freedom to him and 3.5 million enslaved in this country. But, did it grant him equality? Did it level the playing field, break a hole in the fence of opportunity? The records for Caesar - and for millions like him - tell us no, it did not. Despite having some education, despite being by all accounts hard working, intelligent, and kind, Caesar was never able to accumulate land and wealth as his former owners and new neighbors did and had done for centuries. The big fence may have come down, but the others held, and held strong. They held when Johnson abruptly ended Reconstruction, terminating the attempts at equality imposed by the government. They held in 1886 when, in Caesar’s hometown of Jackson, racist mobs dragged Eliza Woods from her jail cell (held for a crime she did not commit), stripped her naked, hung her from a tree on the courthouse lawn, and riddled her body with bullets. The fences held when John Brown was lynched in Jackson in 1891, and Frank Ballard in 1894, and some 4,400 other African Americans between 1877 and 1950. They held as Caesar and his family endured the inequities of the Jim Crow era, watching in fear as sheet-clad, cowardly men burned crosses and firebombed homes and ran a campaign of intimidation focused solely on shoring up the fenceposts. Those fences held throughout Caesar’s 104 years, starkly delineating lines of inequality even as his own great-grandson fought in World War II - a war based entirely upon tearing down fences across the ocean. They held in the years after his death as 1.5 million Black veterans of the War were disenfranchised from benefits of the GI Bill and blocked once again from accumulating wealth and property. Caesar lived through more than a century of fences - stubborn, deep-seated fences - and likely would not have been surprised to see them still alive and well, marking lines in the shadows and impacting lives by the millions, in 1968 when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, only 87 miles from his hometown, slain by a man who was raised inside the fence in Alton, IL, the new home of many of Caesar’s descendants.

Today, 76 years after his death and 180 years after his birth into slavery, our fences are still strong. They divide us racially and ethnically, economically, sexually, religiously, and politically. Rather than being weakened by the test and torments of time, it seems our fences have grown in power and number. White nationalism, supremacy, and extremism is on the rise, increasing exponentially during the Trump era; for the first time ever, the Confederate flag made its way into the Capitol on January 6. The top 5 wealthiest Americans collectively have more wealth ($885 billion) than the GDP of any nation outside of the top seventeen while 38.1 million Americans (as of 2018, likely much larger now) remain mired in poverty, with Native Americans and Blacks having the highest percentage (25.4% and 20.8% respectively, compared to 10.1% for Whites). The list goes on.

A year before his death, MLK spoke to The Hungry Club Forum in Atlanta. The Forum itself was an embodiment of societal fences: The group met in secret, the only means for White politicians sympathetic to the needs of the Black community to meet face to face with Black leaders. King spoke of several fences that evening, evils as he termed them, focusing on racism, war, and poverty. His words on that last fence are especially timely today:

Like a monstrous octopus [poverty] spreads its nagging prehensile tentacles into cities and hamlets and villages all over our nation. Some forty million of our brothers and sisters are poverty stricken, unable to gain the basic necessities of life. And so often we allow them to become invisible because our society’s so affluent that we don’t see the poor. Some of them are Mexican Americans. Some of them are Indians. Some are Puerto Ricans. Some are Appalachian whites. The vast majority are Negroes in proportion to their size in the population … Now there is nothing new about poverty. It’s been with us for years and centuries. What is new at this point though, is that we now have the resources, we now have the skills, we now have the techniques to get rid of poverty. And the question is whether our nation has the will…

- Martin Luther King Jr., America's Chief Moral Dilemma

In the US, we’ve long loved our fences. We build them on our borders, we wrap them around our houses, they wind through our cities and our neighborhoods, we erect them in our cemeteries. Perhaps they offer some comfort, some hint of security, some real or imagined protection from that nascent “other” we are taught to fear. But, more than anything, our fences only divide us, pull us apart, rend the very fabric of our society and our being and our potential for shared success, prosperity, and equality. It’s time we start tearing them down. Let’s do it for Martin Luther King Jr. Let’s do it for Eliza Woods and Elijah Lovejoy, Ahmaud Arbery and Heather Heyer, Chief Joseph and Abraham Lincoln.

Let’s do it for Caesar McClellan, and let’s do it for the soul of our society, for our nation, for ourselves.