To say that Everest has changed in a century is to grossly understate the matter.

Physically, of course, the mountain has changed little. It’s a bit warmer perhaps, and bit less snowy. The monsoons are a bit more erratic. But it still rises high, steeply, to dizzying altitude and, as yet, there is no escalator up to the top - you still need to walk there.

But nearly everything else has changed.

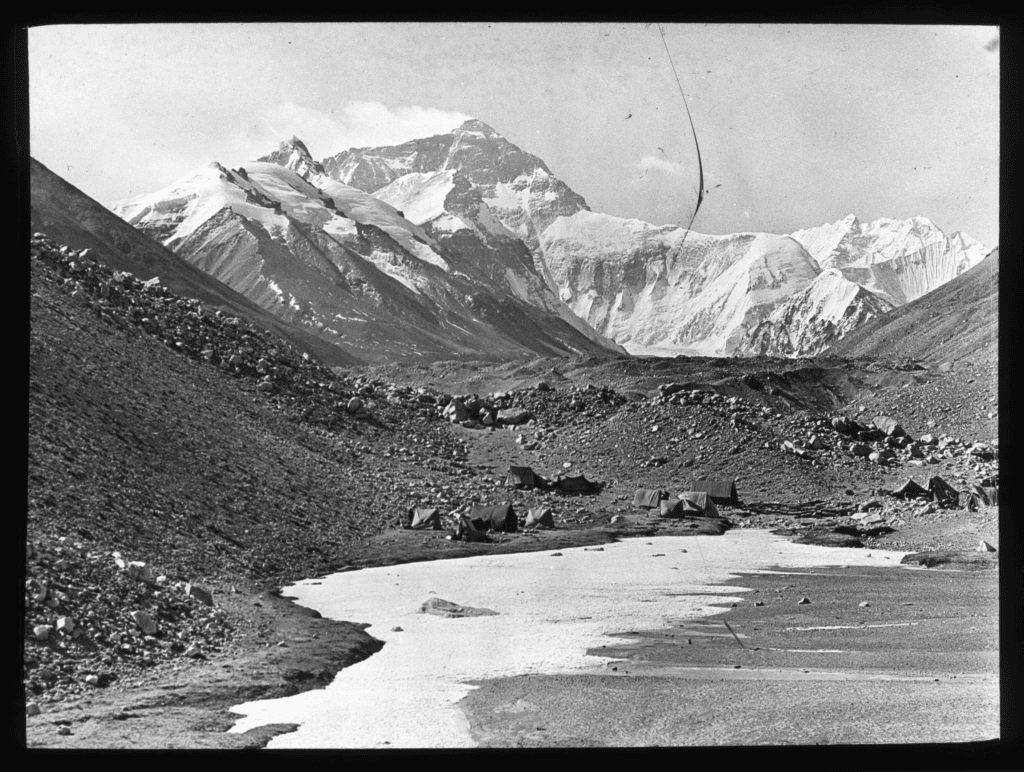

The Everest of today would be almost unrecognizable to a climber from the 1920s. Massive tents at Rongbuk Basecamp replete with (un)necessities like 24/7 hot showers, baking ovens, personal tent heaters, washing machines, and more 5G service than I get at my home. Buses belching bumbling tourists at Basecamp and at Rongbuk Monastery. Robust infrastructure of yak streams stocking camps along the 12 miles from Basecamp to Advanced Basecamp, and a damn-near-continuous string of fixed line running from the foot of the North Col Headwall to the tippy top, even where it is blatantly unneeded.

Everest has changed dramatically while still remaining somewhat the same. (Check out Dave Hahn’s excellent article in Outside Magazine, How Everest Was Turned into an Industry.)

Twenty-five years ago, when I was 25 and making my first foray onto the peak, it fortunately was still a bit more rustic, a bit more of what it was then and less of what it is now.

A few days plus 25 years ago, we had arrived and acclimated at Advanced Basecamp, and it was time to get to work setting the route up to the North Col. As it was the before times, we were able to arrive early, climb early, set the route early, and just get down to business early. (These days, foreign climbers are only allowed into Tibet when Beijing deems it acceptable - which is usually unacceptably late - and are mandated to wait until the CTMA rope fixing team has set the route before proceeding.)

On April 6, 1999, Conrad Anker, Panuru Sherpa, Ang Pisang Sherpa, and I set off to fix line and find a route. Conrad and I hadn’t been to the mountain before, but were feeling good and strong and eager to go. Those who knew it well - our Sherpa team, Dave Hahn, Eric Simonson, Andy Politz - all saw immediately the route to the Col would be a bit different this year than years prior: there was a dearth of snow, exposing more crevasses and ice than usual. It looked to Conrad and I like the best route was a direct one, heading more or less straight up the face.

Conrad and I were chomping at the bit to move, so we went out front, swapping leads and stretching out the rope while Panuru and Ang Pisang helped with anchors and tension. While playing out rope as Conrad let one section, I heard a familiar voice behind me amidst heavy panting: Pryvit Jack. Water? I turned to see my Ukrainian friend Vasily Kopytko handing me his ubiquitous wine skin with a toothy smile. I cracked up, laughing not just because Vasily was pushing wine on the North Col Headwall, but also because he and his team had arrived in Kathmandu only seven days prior and were now pushing up to 23,000 feet. Hard men.

In time, we arrived at a steep section of ice, maybe 65-70° and running for a couple hundred feet. Not overly difficult with modern equipment and ice climbing skills, but made me immediately remember the stories of 75 years prior. In 1924, remembering well the tragic ending of 1922, the climbers decided to avoid the dangerous avalanche-prone sections of the headwall and take a safer route. The catch was the only viable option took them to a massive, scythe-shaped crevasse spanning much of the upper headwall. Upon arriving at the obstacle, Norton and Mallory realized the only option was to drop into the crevasse and climb out again via a deviously steep section they named the “Ice Chimney.” Mallory took the lead:

Confronted with a formidable climbing obstacle Mallory’s behaviour was always characteristic : you could positively see Ms nerves tighten up like fiddle strings. Metaphorically he girt up his loins, and his first instinct was to jump into tho lead. Up the wall and chimney he led here, climbing carefully, neatly, and in that beautiful style that was all his own. I backed him up close below, able now and then to afford him a foothold with haft or head of my axe. The wall, like most walls, was not as steep as it looked and needed only careful step-cutting ; but the chimney, on this our first experience of it, was the deuce, for it was very narrow (it widened later under the influence of a hot sun), its sides were smooth blue ice and it was floored — if the term “ floor ” can be applied to a surface that mounts almost vertically — with soft snow which seemed merely to conceal a bottomless crack and offered little or no foothold. The climb was something of a gymnastic exercise, and one is little fitted for gymnastics above 22,000 feet. I suppose the whole 200-foot climb to a most welcome little platform at the top took us an hour of exertion as severe as anything I have experienced.

- Col. Edward Norton, The Fight for Everest 1924 (read on Archive.org)

Like the ‘24 team, Conrad, Panuru, Ang Pisang, and I got the route through the ice runnel and onward. It was a joy to be out front, our small crew figuring it out, climbing rather than just jugging a line, encountering the risk-reward equation that is part-and-parcel of why one climbs in the first place. Eventually, Conrad ran out of rope about 30 meters from the camp, and we decided it was a good day, a solid effort, and time to descend. A fortunate choice perhaps, as on descent we found our Ukrainian friends had made some dubious changes to our route - shortcutting crevasse end-runs and intermingling/tangling their ropes with ours - requiring additional time and work, assisted by Dave Hahn and Tap Richards.

We ended the day knowing the route was not perfect - it was steep and challenging - but would be doable by everyone, especially with sturdy fixed lines and modern gear. Of course, 75 years prior, their steep bits were more problematic: they had no crampons (that were truly functional), limited rope for fixing, and their porter team had very limited experience. The Ice Chimney would prove a difficult, daunting, and dangerous place.

That is, until the ingenuity of Andrew Irvine came into play. On May 27, as the team prepared to launch the first summit attempt of Teddy Norton and Howard Somervell, they chose at Camp II the “Tigers,” the porters “on whom now all our hopes centred,” as they would be the keystone to getting Camp VI at 27,000 feet established. But, the question of the Chimney remained, and how would laden porters safely climb it, getting essential equipment up the mountain. Enter Irvine and Noel Odell, a bunch of Alpine rope and spare tent pegs, and - voilà - a 70-foot rope ladder was birthed and soon put in place.

We didn’t need ladders in 1999 - metal or rope - nor were we cutting steps in hobnailed boots. But, ‘99 was a bit of a different time on the hill - thankfully - reminiscent of the early days, it was a time when we could climb as climbers, set our pace and timing and operate as we needed to, rather than how we were told to (as is more common today on the North), to climb and move and explore where we needed, where we wanted. That freedom continued throughout our expedition, enabling the movement and nimbleness essential to do what we were there to do, a step up the mountain for a step back in time.

So much has changed, but in 1999 at least, some remained the same.

That route to the North Col in 1999 was an inspiring piece of climbing through a beautiful landscape, and I still remember many passages of it vividly 25 years later. Time for more shared memories soon!

Cannot wait to see you soon, my friend! Lots to remember, and good new memories to create!