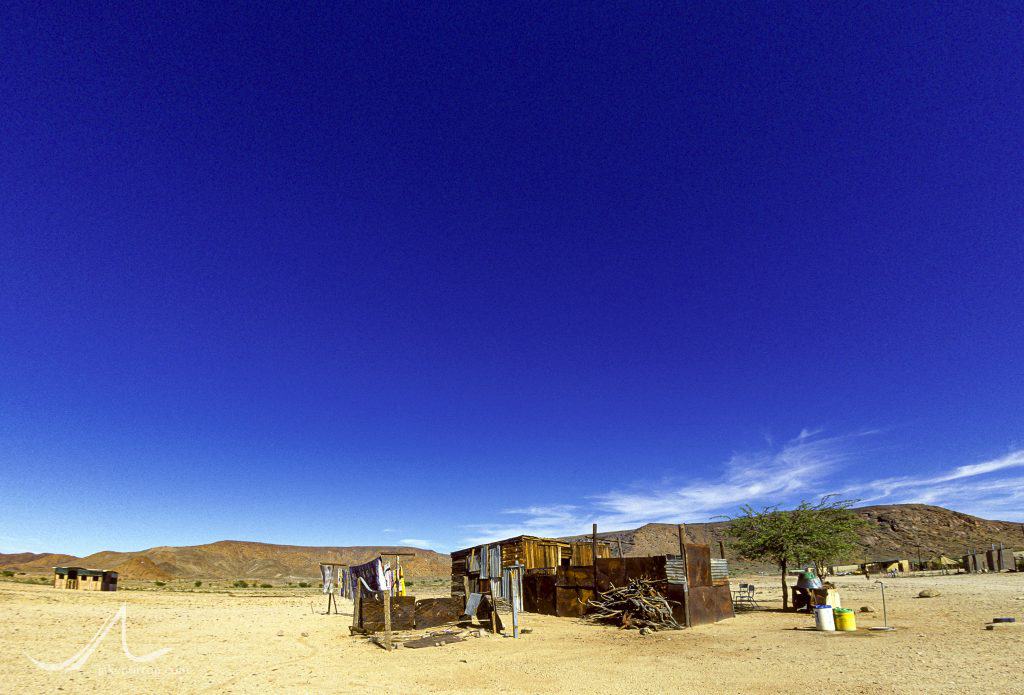

The wind whipped at me, but it wasn’t a welcoming, cooling wind. It was the wind of a blast furnace, churning hot and dry, spitting out dust devils and twirling bits of plastic across the charred landscape. It was only 10:00 AM, and already the temperature was 40° C (104° F), and was projected to hit 49°+ (120° F) by afternoon - hot enough to cook an egg on a dark stone. (Trite, I know, but true - I tried it with success the day before.) As the infernal wind relentlessly flapped corrugated tin on ramshackle houses, I wondered to myself: “How could anyone live here?”

Wandering around the village of Riemvasmaak - a tiny, desert hamlet in the Northern Cape of South Africa, a stone’s throw from the Namibian border - I snapped photos and attempted to interact with the shy villagers peering warily, distrustingly, from tin shacks and squat, cement buildings.

I understood their distrust, for the history here is a rough one. The name alone - Riemvasmaak - refers to the story of local Bushmen in the early 1900’s who rustled cattle, were caught, and subsequently tied with riemes, or straps, to a large boulder in the dry Molopo River. The next day when locals went to check on the men - expecting to find them dead of exposure - they were gone, having escaped their loose bonds during the night. Hence, Riemvasmaak, or “tighten the straps.”

Originally settled around the 1930’s by members of the Xhosa, Damara, Herero, and Nama tribes, as well as Coloured pastoralists, these pioneers survived and then flourished, scratching communities and churches in the harsh, volcanic landscape. But, in the early-1970’s, the South African apartheid government took the land, forcibly removing all inhabitants, and turned it into a military testing site. The people were scattered, relocated with no compensation across the region. It was not until 1998, after the fall of apartheid and the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, that Riemvasmaakers were finally allowed to return.

From the corner of my eye, I saw movement. A thin arm waved from the shadows of a tin portico, beckoning me over. I obliged, and was soon greeted by a warm and welcoming smile and offered a dusty chair in the shade.

“I am Peter Lord. Welcome to Riemvasmaak,” he said in heavily-accented English, a grand smile expressing what his dermatochalasis-obscured eyes could not. “Why are you here?”

I explained briefly my reasons, that I was shooting for a reality television series called Global Extremes, covering athletes who were racing through his region on foot, bike, and camel. He smiled one of those polite-but-you’re-weird smiles: “We’re happy you’re here. People didn’t used to come here.”

He told me the story of Riemvasmaak, and his personal part in it. Evicted from his home without cause in 1972, he and his Damara people were sent packing to Namibia, where they were tolerated, but not truly welcomed. For twenty-six years he lived in Namibia, a semi-nomadic existence of hand-to-mouth survival, watching family members die far from home and new generations come into the world homeless.

“But, now, I’m back,” he said softly. “For five years now, I’m back.” His smile again crinkled his face, obviously elated at the very thought of it all, the reality of being home again.

“That’s wonderful, Peter,” I said. “But, aren’t you angry at all after all you and your family went through? Don’t you want revenge”

The smile disappeared, replaced by a quizzical look, an amalgam of confusion at my question and sorrow at the notion. “Why would I be angry? I’m alive, and I’m home.”

We bade each other goodbye, Peter retreating into the shade of his home as I headed off, shielding my camera and eyes from the wind-driven dust. My mind spun, trying to reconcile the utter lack of anger in Peter, his true happiness to be home overtaking any lurking desire for retribution. It was a somewhat foreign concept to me, born and raised as I was in a society often focused more on settling scores than doing right.

Before meeting Peter, I would have thought his reaction to the hardship he was put through was spineless, wimpy even. He had every right to be pissed off, to be filled with fury, anger, hatred…and to act on those emotions to seek vengeance. But, spending time with him in the shade of his home, I knew he was anything but spineless, far from wimpy. Peter was a fighter: 26 years in Namibia proved that, as did his 80-some-odd years of life in a region that always treated him as an inferior. Rather than spineless, wimpy, I realized Peter was one of the most courageous people I had ever met, for he faced hatred and mistreatment and anger and oppression not with vitriolic outpourings of the same, but instead with love and compassion and moving onward in life with his chin held high, his character and person unsullied by the vileness he had endured. This attribute - relentless forgiveness coupled with impeccable optimism - was, I realized then and there, the truest sign of courage, of strength, of character.

Seventeen years later, Peter’s smile and being come to me often, visits from the ether reminding me of the lessons learned in Riemvasmaak. And, I believe, Peter’s story, his unintentional message, is more poignant today in our time of strife and division than ever before. On the first page of a favorite book, Shantaram, Gregory David Roberts writes:

It took me a long time and most of the world to learn what I know about love and fate and the choices we make, but the heart of it came to me in an instant, while I was chained to a wall and being tortured. I realised, somehow, through the screaming in my mind, that even in that shackled, bloody helplessness, I was still free: free to hate the men who were torturing me, or to forgive them. It doesn’t sound like much, I know. But in the flinch and bite of the chain, when it’s all you’ve got, that freedom is a universe of possibility. And the choice you make, between hating and forgiving, can become the story of your life.

Freedom. Freedom to forgive. A universe of possibility…if we can find the strength to see it, to embrace it.

Decades earlier, Albert Camus - the great existential philosopher and Nobel Prize winner - penned the following, a brief but prescient ode to the universe of possibility and the unbreakable human spirit:

My dear,

In the midst of hate, I found there was, within me, an invincible love.

In the midst of tears, I found there was, within me, an invincible smile.

In the midst of chaos, I found there was, within me, an invincible calm.

I realized, through it all, that…

In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer.

And that makes me happy. For it says that no matter how hard the world pushes against me, within me, there’s something stronger – something better, pushing right back.

Truly yours,

Albert Camus

Extraordinary! Inspiring! Beautiful! Thank you.

Thank you, Aiya!

Thanks so much for writing this, Jake.. South Africa has my heart, more than any other country I've spent time in. I was there for the first election and met many Peter Lords!

Thanks, Meg, and I would love to hear the stories of your time in South Africa! I've only been that one time, but would love to go back. Thank you, and hugs to you all, and stay healthy, happy, and safe!