When my son, Ryrie, was younger, he would pore for hours (no exaggeration - he’s always had an impressive attention span, even at age 6) over his favorite book, a short picture book about a quirky but fascinating man, Wilson Bentley, and his obsession with photographing snowflakes. Snowflake Bentley (library access) tells his story in pictures, and his dedication to sharing with the world the beauty of snow. (Dive deeper if you want with Maria Popova's article on Bentley and his work.)

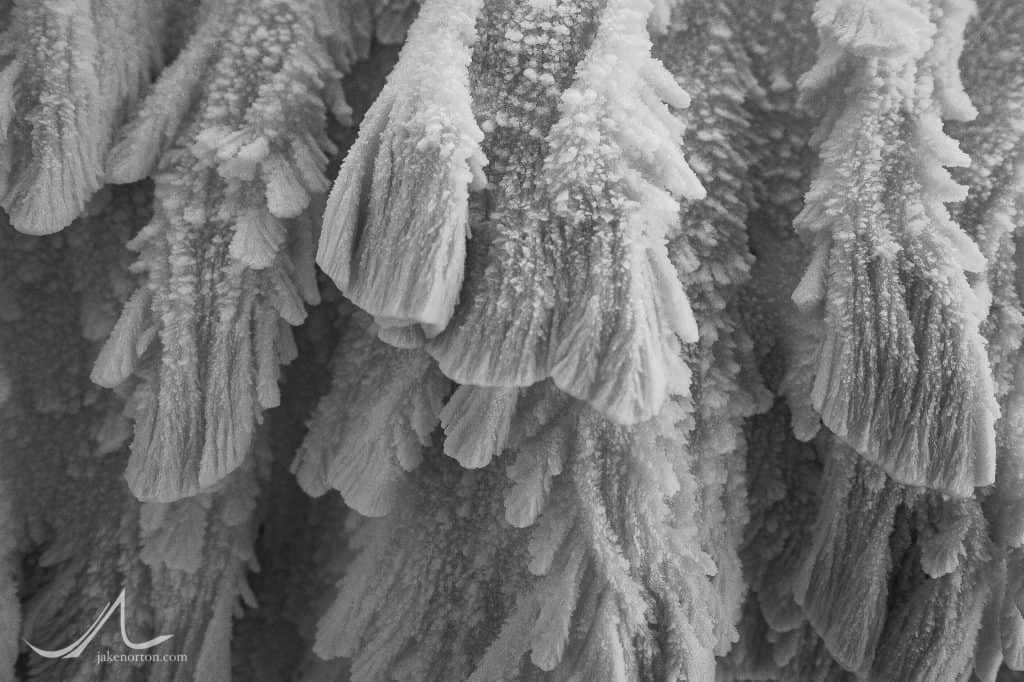

Like Bentley, like Ryrie, I’ve been thinking a lot about snow recently. Perhaps it’s simply due to our utter lack of it so far this winter, the dulled browns of tree and field wearing on me, burdened under the fear of another fierce fire season should we not get more moisture. But, it’s more than that. There’s a sublime beauty, an entrancing peace and imposing bliss brought by snow. Just watch flakes falling gently, bobbing and weaving on unseen and unfelt currents, anchoring on the spike of a pine needle, snowflake’s brilliant white a mystical contrast to the deep green of the needle. Listen to the deep, reverberating, penetrating silence of a snowfall at midnight, muting the auditory chaos of our world and allowing the mind a brief respite of quiet. Awaken to the luscious, pillowy blanket of a blizzard’s bounty, and watch the unbridled, indefatigable joy and play of children (and sometimes adults) in that same blanket. Catch a flake for but a fleeting instant and see its spellbinding intricacy, six points of crystalline sculpture, a masterpiece of nature never repeated, disappearing in an instant.

Over decades spent in the high country, crossing crevasses and sidestepping cornices, enduring the ferocity of a blizzard and the peace of a gentle squall, snow has been my constant companion. I’ve marveled at its dichotomous transience-cum-permanence, how a single flake is frailty inherent, while when gathered by the billions those same flakes can bridge a crevasse, tumble ferociously in life-destroying avalanche or icefall, crush a ship and carve a canyon. Perhaps more than any other visible, tangible element, snow and snowflakes are stuff of mystery, beauty, nature’s wonder in its sublimest form. In The Immense Journey, Loren Eiseley summed it up:

No utilitarian philosophy explains a snow crystal, no doctrine of use or disuse. Water has merely leapt out of vapor and thin nothingness in the night sky to array itself in form. There is no logical reason for the existence of a snow-flake any more than there is for evolution. It is an apparition from that mysterious shadow world beyond nature, that final world which contains—if anything contains—the explanation of men and catfish and green leaves.

- Loren Eiseley, The Immense Journey: An Imaginative Naturalist Explores the Mysteries of Man and Nature (library access)

Aside from the beauty of snow, aside from its ability to create and destroy, there is something deeper, more profound about these tiny droplets of water, transformed by temperature into sculpture divine. Maybe it’s that they remind us of our own astonishing power - especially when we join in vast numbers - and also of our inherent frailty, our impermanence. Like snowflakes, we humans are each a remarkable, unique, irreplicable work of art, astonishing in our transformation from simple droplet to stunning complexity. Individually, we’re strong, yet frail; gathered as a collective, our power grows exponentially, capable of creating remarkable change, massive destruction, stunning inertia.

And, through all of this, we - like a snowflake on an outstretched palm - are tragically impermanent. No matter our individual beauty, the intricacies of our crystals, our efforts to connect to others or stand in isolation, our existence on this planet, in this form, is painfully, tragically, beautifully short. From the moment of our birth, we all begin to melt, some - by chance or choice - more quickly than others. But, melt we all do, we all will, dissolving into the next chapter, the next phase, the next iteration, whatever that may be. Yet again, like the snowflake, our physical disappearance or transformation does not mean our memory, our spirit, some aspect of our substance and being is gone, too, for like the snowflakes captured by Bentley a century ago, they are long gone physically, but not in any way forgotten, utterly insignificant in their inherent significance.

Once more, I turn to the wisdom and words of Eiseley and his poem "The Snowstorm":

‘It is the first and last snows – especially the last –

- Loren Eiseley, "The Snowstorm," from The Innocent Assassins (library access)

that blind us most,’ Thoreau once said, and I wonder

what he possibly could have been thinking since snow

is always with us and keeps falling

in its proper season,

the generations accepting it without first or last

save perhaps this:

There is a single snow which a child

stores in his memory, the first

snow when he falls in a drift, the first

snow that reveals secrets

like the flake on his sleeve

always to be remembered because it brought

knowledge of crystalline perfection, infinite diversity to be tested

with his own salt tears,

the immeasurable prodigality

of the universal worlds in which we are lost,

the first and blinding snow of childhood.

Second,

The view from the farm window, the last,

with the black guest

waiting at the door

and outside

falling and falling

across corn shocks

wheat stubble

plowland

the whiteness of the void. Lucretius must so have seen his atoms,

created

out of them a world. A wind whipped the flakes aside, perhaps,

a snow flurry that conceived

a farmhouse kitchen

and a stove,

made fields,

made animals,

made men.

Look, can you say I am not composed of snowflakes?

My eyes are filled with them.

They are falling faster now.

Suppose I go

outside and join them.

Could you say that I

was ever here? No, no. The first blindness is to see the ultimate minute perfection.

That is the illusion of the water drop.

The second is to believe

the black guest at the door.

My friend,

there is only the blindness of a million years of snowfall,

and you and I

wraiths, wraiths, discoursing as we fall.

Do not bother to throw up the window,

snow is already blowing

the room is disassembled,

our substance,

the room’s substance, is snowflakes;

we are falling apart now,

we have re-entered

the eternal storm.

Finally, a nice short film on the life and work of Snowflake Bentley: