It’s been almost 100 years - we’ll hit the centenary this Saturday, June 8, 2024 - since George Mallory and Andrew Irvine famously vanished in the mists less than 1,000 feet from the summit of Mount Everest. Their disappearance understandably sparked a century of debate - a debate which continues rigorously to this day - surrounding the greatest mystery of exploration: Did they reach the top of the world on that day, 29 years before Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay did so from the Nepal side?

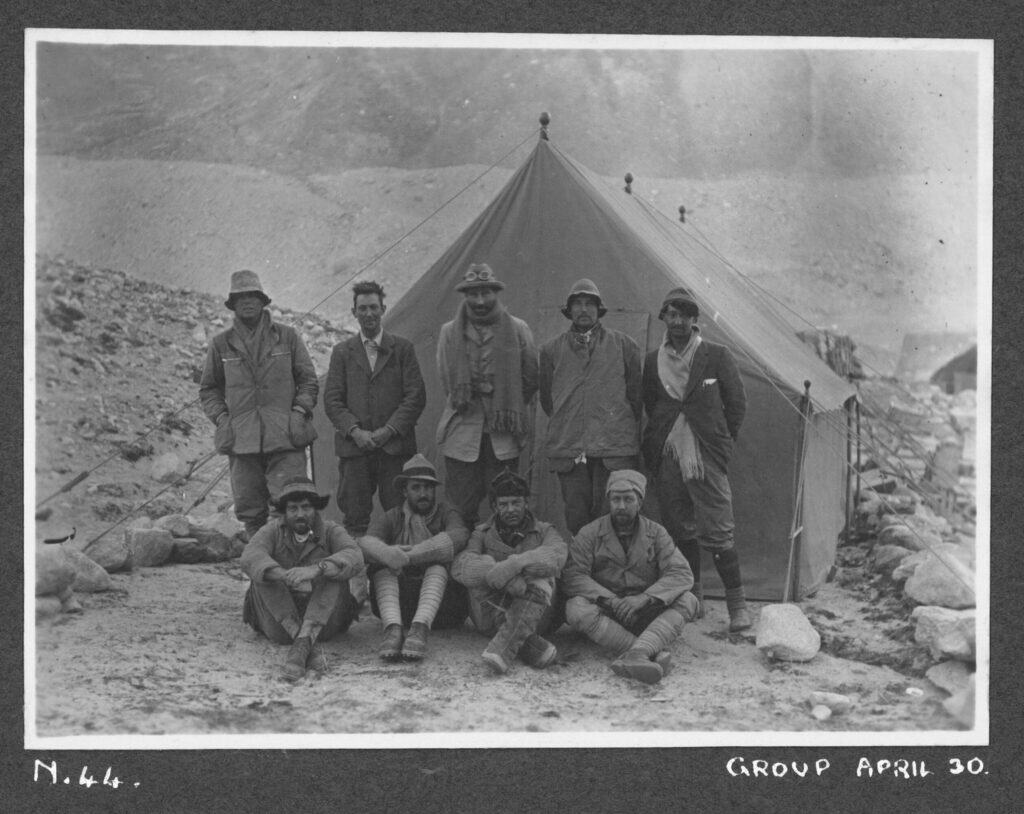

But the discussion of, and fascination with, the story of Mallory and Irvine and their ultimate fate has overshadowed another remarkable event that occurred 100 years ago today: the oxygenless summit attempt by Edward “Teddy” Norton and Howard Somervell on June 4, 1924.

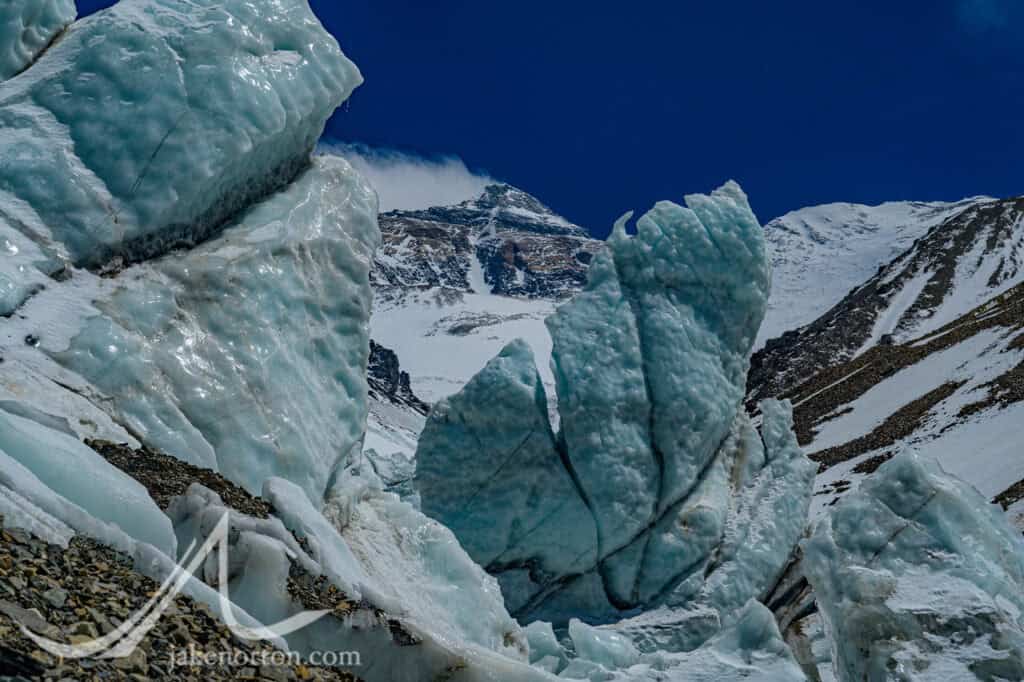

I won’t go into all the details here as I’ve written about it quite a bit in the past (see Everest 1924: Norton & Somervell's Record Attempt). In a nutshell, Norton and Somervell set off from Camp VI on the morning of June 4, angling across the North Face and traversing the Yellow Band beneath the First and Second Steps, aiming for the Great - or Norton - Couloir. Somervell, having frostbitten his larynx days before, was not feeling fully up to snuff so he stopped at roughly 28,000 feet. Norton continued onward into the Couloir, finally turning around in miserable snow conditions at 28,125 feet. In The Fight for Everest (on Archive.org), Norton described it thus:

It was not exactly difficult going, but it was a dangerous place for a single unroped climber, as one slip would have sent me in all probability to the bottom of the mountain. The strain of climbing so carefully was beginning to tell and I was getting exhausted…I had perhaps 200 feet more of this nasty going to surmount before I emerged on to the north face of the final pyramid and, I believe, safety and an easy route to the summit. It was now 1 p.m., and a brief calculation showed that I had no chance of climbing the remaining 800 or 900 feet if I was to return in safety…

- Edward Norton, The Fight for Everest (Archive.org)

While unsuccessful in the traditional sense, Norton set a world altitude record that day, and an oxygenless altitude record that would stand another 54 years, beaten only in 1978 when Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler climbed Everest from the South Side without bottled oxygen. (N.B.: Messner and Habeler beat Norton’s record, but did so on a known route and were not wearing woolen knickers and hobnailed boots! And, while Somervell didn’t go quite as high as Norton, 28,000 feet is nothing to shake a stick at, especially with a frostbitten larynx.)

So, suffice it to say, what transpired four days before Mallory and Irvine’s disappearance was quite astonishing and deserving of more attention that it receives. And, their remarkable climb, in my mind, is made even more impressive because of the record Norton (and Somervell) did not set, the spot on the mountain they did not reach: the summit.

Like all members of the 1924 expedition, Norton and Somervell were strong, focused, driven climbers. They wanted to be there, wanted to climb high, wanted to climb Everest and reach the summit. But, unlike at least one of their teammates, Norton and Somervell did not need the summit of Everest. They both had engaging, promising careers to which they were dedicated; Norton as a military man and Somervell as a surgeon. For them, Everest was an adventure, an opportunity to engage in a pastime they loved, to struggle and push and see what they could accomplish…and then go back home to their families and their careers.

Reflecting on their inability to reach the summit on June 4, neither man seemed much perturbed by it. Norton wrote in The Fight for Everest (on Archive.org) that he had “but little feelings other than relief that the strain and effort of climbing [were] finished.” Somervell went a bit deeper:

There is nothing to complain of. We established camps; our porters played up well; we obtained sleep even at the highest altitude, nearly 27,000 feet, and we had gorgeous days for the climb, almost windless and brilliantly fine, yet we were unable to get to the summit. So we have no excuse. We have been beaten in a fair fight - but the fight was worth it every time, and we shall cherish the privilege of defeat by the world's greatest mountain.

- Howard Somervell from The New York Times, quoted in The Nation, July 9, 1924

Years later, Jochen Hemmleb would speak to Norton’s son, Hugh, who summed it up perfectly: "My father did not need the summit. He had a fulfilling life as a professional soldier and saw his Everest expeditions as just an extraordinary 'diversion' from it.”

Thirty-nine years after Norton and Somervell, my late friend and hero, Tom Hornbein, made a remarkable ascent of Everest with Willi Unsoeld via the West Ridge, redefining the notion of possible in the high Himalaya. But, like Norton and Somervell, Tom climbed the mountain because he wanted to, not because he needed to. As Tom wrote in his wonderful book Everest: The West Ridge:

What possible difference could climbing Everest make? Certainly the mountain hadn't been changed. Even now wind and falling snow would have obliterated most signs of our having been there. Was I any greater for having stood on the highest place on earth? Within the wasted figure that stumbled weary and fearful back toward home there was no question about the answer to that one.

- Tom Hornbein, Everest: The West Ridge

Fast forward to today: It takes but little effort to view the chaos and concomitant carnage that is part and parcel to Everest these days. A two second Google search yields sickening, terrifying images of queues on the summit ridge that resemble Black Friday Walmart lines. As another Everest season wraps, we’ve added eight more entries to the list of Everest deaths, bringing the total since 1921 to 340.

I obviously cannot speak for those lost, for their motives and goals and perspectives. But I can’t help but wonder if some of them - maybe a lot of them, and maybe a lot more who got away with it - decided, like George Mallory did 100 years ago, that the summit of Everest, the patch of snow on top of the world, was somehow something essential, transformative and transfigurative, a thing they needed, not simply something they wanted.

The sad truth, as Teddy and Howard thought in 1924, and Hornbein experienced in 1963, is that the summit does not transform or transfigure. No, the truth of Everest is the truth of all mountains, the truth of all we do in life: it is the process and the journey and the struggle and the battles we fight internally and externally…these are the things that transform, transfigure, inspire and inform us, the things that give us purpose and meaning. The summit? It is and always has been just a patch of snow, nothing more and nothing less.

The sooner we can embrace that reality, be it on Everest or in a boardroom or in the monumental climbs of our internal lives, the sooner we all can enjoy an “extraordinary diversion” ending in “the privilege of defeat.”

Gorgeous, and well said. Thank you.

Thank you, Angela.

Thanks Jake

I have always had the highest regard and admiration for Norton and Somervell's climb and their decision to pull back at the right time!

Thanks, Sujoy!

Sometimes it is the people who go under the radar that emerge as the victors .i have so much respect for these two climbers .Great piece thank you 🙏.

A great reminder for all of us. Sadly, I fear there is no medicine that can cure the fever some seem to be born with, but I hope what you've written here will at least cause them to take pause and consider this truth.

Thank you, and I hope so, too! Be well!