Note: I’ve been going through tons of old images from Everest these past weeks while building out a massive series of interactive panoramas of the mountain. This project has taken on a life of its own, taking me (and you, once I’m done) around the mountain and its environs, taking deep dives into history, routes, facts, and stories. This story popped itself out at me this morning - perfect for today's "Moments, Memories, Mountains" post . Enjoy!

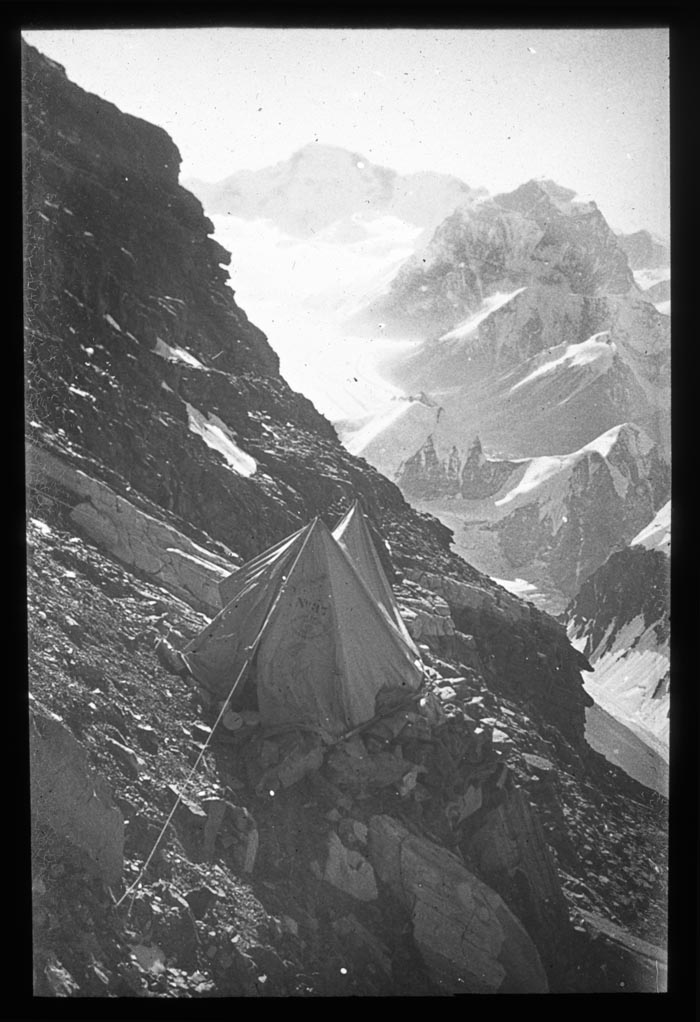

Camp V on Everest’s North Ridge is a rather brutal place. It’s notoriously cold and windy - I’d argue the coldest and windiest place I’ve visited on Everest, or anywhere - and rarely fails to bring on a headache to rival any hangover. Time spent in Camp V is more ordeal than experience, more pain than pleasure, definitively cemented in the realm of Type 2 fun, perhaps bordering on Type 3.

The morning of April 28, 2001, was no exception. Brent Okita and I awoke to the bone-numbing, soul-freezing, all-penetrating cold of 25,600 feet, a fresh dusting of snow outside the tent and stalactites of ice clinging precariously inside, crystalline remnants of the prior night’s breath wanting nothing more than to fall into the morning’s water heating on the stove. Inertia often becomes an unwanted guiding principle at high altitude, sapping motivation and encouraging lethargy at every turn. Brent and I battled to get up and get going but eventually won against our own weakness and stepped out of the tents.

I’ve always been amazed by how much change is brought by a simple action, how completely inertia is replaced by enthusiasm once we muster the courage to take the first step. As I emerged from our nylon cocoon into the stunning beauty of Camp V, my desire to lie about in my sleeping bag waned quickly, and excitement for the day grew exponentially.

Above our small camp, the climbing route to Camp VI (27,200 feet) followed the geologic catastrophe of the North Ridge - more an unfortunate pile of shattered rock than anything resembling an Alpine ridge - for a few hundred feet before deviating south across the north face to a small runnel of snow leading upward. Our route for the day would be different: when the main route doglegged right, we continued straight, navigating the rubble and fractured towers of the North Ridge proper another 1,000 feet to look for the 1924 Camp VI, last occupied by George Mallory and Andrew Irvine on the night of June 7, 1924.

The climbing was not exactly difficult; "interesting" is a more apt description. On the normal route of the North Ridge, slips are common as the points of crampons tend to disagree with the loose rubble sitting atop downsloping slabs, skittering out rather than gaining purchase, and sending the climber in awkward directions. On the route, though, fixed lines are the norm and, while not always bomber and not always fully intact, they offer a backup, a handrail on which to regain lost balance. For Brent and me, the terrain was similar - perhaps a few degrees steeper - but with no route and no fixed lines; attention and focus was paramount, for a fall here would be hard to stop, and the consequences considerably unpleasant.

We knew little about where the 1924 Camp VI was located. Our resident historian, Jochen Hemmleb, believed it to be near the top of the steep part of the ridge, just below 27,000 feet. We could logically assume it would be slightly to climber’s left of the crest of the ridge, maximizing the ridge’s natural windbreak to protect the tiny A-frame tent, and the original expedition chronicle - The Fight for Everest 1924 (library access) - noted the camp was in “a narrow cleft in the rocks facing north and affording the suggestion - it was little more - of some shelter from the north-west wind.” In ‘24, they estimated the altitude to be about 26,800 feet, although we suspected it might be a bit higher than that.

As Brent and I meandered up the Ridge, picking the path of least resistance, I kept trying to put myself in the mindset of Teddy Norton and Howard Somervell, who established the camp on June 3, 1924, with huge help from porters Norbu Yeshe, Lhakpa Chede, and Semchumbi: Where would they climb, in woolen knickers and tweed coats and hobnailed boots? What features on the Ridge would they seek out as suitable for a camp, high enough to launch a reasonable summit attempt while still maximizing protection from the ferocious wind? As we climbed, Jochen assisted via telescope and radio from Basecamp, letting us know what features lay above, lost as they were to our vision in the labyrinth of the Ridge.

Choosing a path of logical feasibility upward at about 26,900 feet, I spied a pointed gendarme of rock not high above; via radio, Jochen confirmed it being in the right location and altitude. As I approached, it seemed to fit the bill: the right altitude, and a flat-ish spot at its base somewhat protected from the wind. (In Fight for Everest, Norton described the total lack of tent spots on the North Ridge well: “I can safely say that in two excursions up and down the whole length of the North Arete of Mount Everest I have never seen a single spot affording the six-foot square level area on which a tent could be pitched without having to build a platform.”) As I got closer, however, it seemed less likely, for the gendarme’s base was not at all flat, and no realistic spot for even a single tiny tent was evident. And then I looked down, spotting a bit of wood poking from the black-rock rubble: it was a tent pole, lying for 77 years in the rubble of what we now understood to be a largely collapsed tower. We had found the camp and began to investigate.

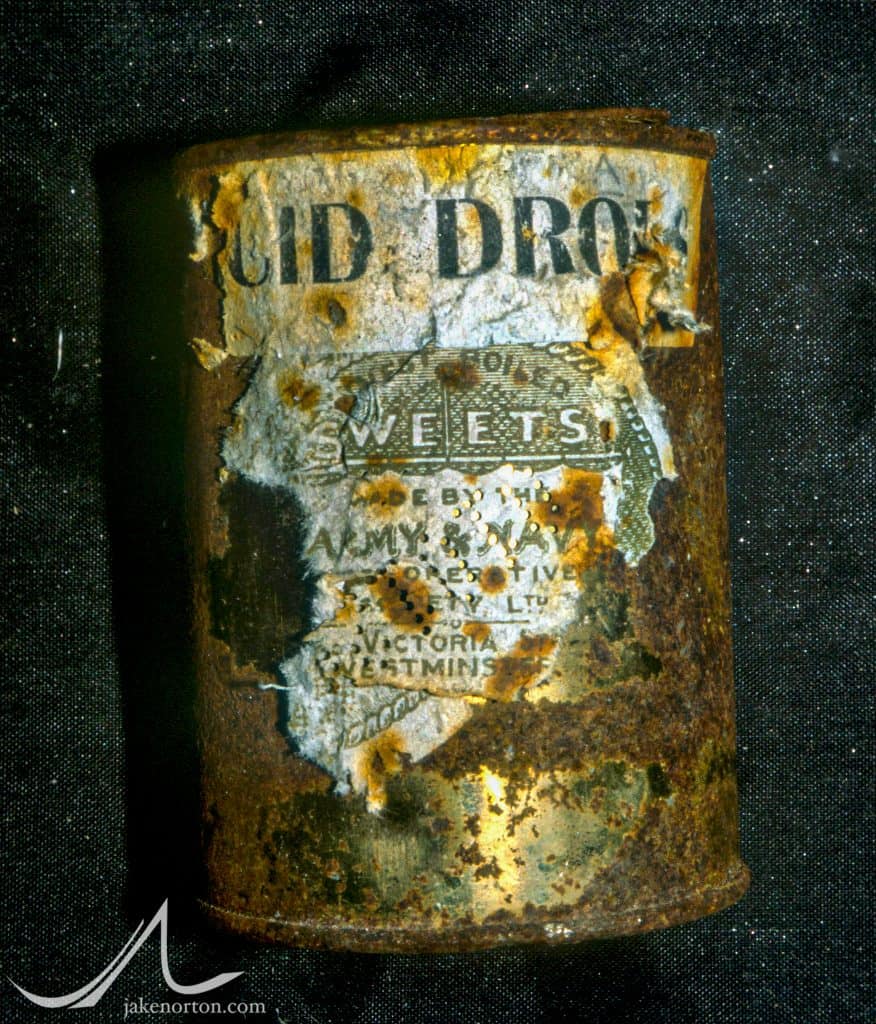

Not much was left as best we could tell: decades of wind and storm, erosion and weather had taken their toll, reducing the remains of the camp to mere bits and pieces hidden in rubble. Brent and I dug around, moving rocks and scratching through frozen gravel, slowly unearthing tidbits of history, artifacts from the final summit bid of our heroes, beautiful scraps of the past somehow surviving to the present. Along with the tent pole, we found 6 wooden matches and solid meta-fuel from the stove, shredded remnants of the tent and its guylines, leather strapping likely from an oxygen system, a woolen mitten, an Acid Drops candy can full of loose-leaf tea, and a single tattered sock with a tiny laundry label stitched on the side.

The label read simply “NORTON.” It was, of course, Colonel Edward Felix “Teddy” Norton’s sock, likely abandoned after a water bottle uncorked itself during the night of June 3, soaking his sleeping bag and this one sock: a near Norton tragedy in 1924, and another Norton’s boon in 2001.

A tin can full of loose-leaf tea, recovered by Jake Norton from the tattered remains of the 1924 Camp VI at 27,000 feet on the North Ridge of Mount Everest, Tibet.

Artifacts recovered by Jake Norton and Brent Okita from the 1924 Camp VI at nearly 27,000 feet on the North Ridge of Mount Everest on April 30, 2001. From top: wooden tent pole; fragments of a second tent pole; fabric from tent; guylines for tent. Photo by Jochen Hemmleb.

Colonel Edward Felix "Teddy" Norton's sock recovered by Jake Norton from the 1924 Camp VI at nearly 27,000 feet on the North Ridge of Mount Everest on April 30, 2001, with fellow climber Brent Okita.

Artifacts recovered by Jake Norton and Brent Okita from the 1924 Camp VI at nearly 27,000 feet on the North Ridge of Mount Everest on April 30, 2001. Clockwise from upper left: Teddy Norton's sock; tin can of "Acid Drops" filled with tea; stove part; matches and meta-fuel; leather oxygen system strapping; woolen mitten. Photo by Jochen Hemmleb.

Tin can of "Acid Drops" filled with tea recovered by Jake Norton from the 1924 Camp VI at nearly 27,000 feet on the North Ridge of Mount Everest on April 30, 2001, with fellow climber Brent Okita. Photo by Jochen Hemmleb.

Additional artifacts recovered from the 1924 Camp VI on a second search by Andy Politz, Dave Hahn, and Tap Richards, including additional tent poles, tent pieces, tin cans, and an old spoon. Photo by Jochen Hemmleb.

Great history and not sufficiently appreciated.

Thanks, Tom, and thanks especially to you for all your tireless work on Everest history for all these years!

Jake, your exploits, and successes, and later your understated stories about them are treasures for the rest of us down here at much lower altitudes. You and your remarkable clan of fellow climbing partners give us the richest stories we could imagine, here in our warm, secure (and level) living rooms. Thank you for sharing such wonderful, most excellent adventures with us.

Thanks, Mike, as always, for your love, support, and kind words. It means a lot, especially coming from you! And, while not literally there, you were there in so many ways on those wild expeditions, and a part of the story as well. I hope you're well and healthy, and hope to see you again as the dust settles some.

Jake,

One feels a deep respect and awe for these Everest pioneers 🙏🙏🙏 thanks for bringing this to life

Thanks, Sujoy, and glad you enjoyed the post. Those pioneers all deserve a ton of credit! Thanks again, and be well. 🙏

As a history buff and keen observer of the 1924 expedition, this is great stuff.amazing anything still remians.

Your effort in finding mallory in 99 was incredible.

Cant stop speculating on their fates.

Cheers Alex from Australia

Hi again, Alex,

You're like me - the story, the nuance, the mystery, gets a hold of you and doesn't let go! So much still to learn, ponder, and hopefully one day know more about!

All my best,

Jake

Hi Jake,

Do you think that there was more to be excavated of camp VI underneath the frozen rubble? Namely the oxygen cylinders Odell reported having seen inside the tent. Would be a great clue/confirmation of Mallory and Irvine's oxygen strategy based on the Stella letter notes.

Best,

Darren

Hi Darren,

I'm doubtful there is more up at the site, unfortunately. When I found the camp in 2001 with Brent Okita, we didn't have a metal detector with us (or tons of time), so we did a quick scour of the area, finding the tent pole (which told us first this was indeed the camp), Norton's sock, and some other bits and pieces. Later, Dave Hahn, Andy Politz, Tap Richards, and John Race returned to the camp with more time (knowing where to go) and a metal detector, and did a pretty thorough scan of the area, finding a lot of other bits and pieces, but nothing of major significance. That said, there could of course be things hidden further below the camp location, or perhaps off to the leeward side toward the NE Face. I'm honestly not sure how far and wide the team searched outside of the immediate vicinity, and of course the rock of the N Ridge is really a grand rubble pile, so it's quite possible items like an O2 bottle could have slithered down the mountain some. That said, I still am doubtful of an O2 bottle would have been missed by our 2001 team - but not impossible! That would be a great find!

Ah that's a shame.

I had sort of expected that given there were probably 5 bottles at the camp in 1924, some would still be there if other parts of the camp had remained in place. I always found it odd there was no mention of O2 bottles by the 1933 expedition when they came across the camp, or from any subsequent expedition visits.

Perhaps worth a further search in the future, particularly as it seems to be in a relatively safe location compared to remaining 'priority' search areas. Although that's purely armchair speculation on my part as I've never been to Everest!

Best,

Darren

Thanks, Darren. I would love to get there again, someday. I'm sure there are still bit and pieces hidden around the mountain, waiting to be found. As for the O2, Odell did bring a set down from Camp VI in '24. As I understand it, he turned it over to the RGS, which has not seen it since. Perhaps it's hidden away in a dusty corner somewhere like the Ark in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Would love it to be rediscovered someday!

Hi Jake,

I love it! Nothing like finding something largely unvisited for so long. Speaking of such, has anyone besides you visited 1924 VI in the past? Chinese? British 33 or 38? Which was the higher camp-33 or 38? And compared to 24?

As to the sock, didn't one of the climbers have a cold foot and was recommended to remove one of the (four?) socks on that foot? Did you drink any of that tea?

Hi Arne,

Thanks for the note and questions, and glad you liked the post! It was a true joy to find that camp and the little bits that still remained there. As for other visitors, I know the '33 and likely other expeditions of the '30s visited it. The Chinese didn't really speak to visiting it specifically in 1960 or 1975, but I would be surprised if they did not on one of those expeditions.

As for the higher camp, '33 was definitely the highest of the pre-WWII camps by a good margin.

Thanks, and look for an announcement - hopefully today - for the opening of my Mallory & Irvine community and forum!

Hi Jake

I really enjoy your work. I just read Edward's book where he claims that the M&I C6 was moved or established as a new C6 higher up at 27,300 feet. As I understood him, he got that information from John Noel's boom from 1927. Do you think this i likely? And if so, that might be the answer to why no O2 cylinders or other O2 equipment was found.

Best regards Oddbjorn from Oslo, Norway