The tune rolled out, cheery, whistled notes somewhat muted both by the heavy air, roiling with humidity, and the somber locale, catty corner to the 16th Street Baptist Church.

I just called to say I love you

I Just Called to Say I Love You, by Stevie Wonder

I just called to say how much I care

I just called to say I love you

And I mean it from the bottom of my heart

Eyes smiling and steps springing despite the swelter, Tony Crawford sang as he walked up to us in Kelly Ingram Park. “Now that’s an impressive man,” Tony said, gesturing to a statue of Martin Luther King, Jr. “But my hero, he’s over there. You don’t hear about Fred Shuttlesworth as much, but he’s the one that made the change happen.”

We walked with Tony as he told us about Shuttlesworth, King, and his experiences and life growing up a handful of blocks away, witness to and participant in the trials, horrors, and progress of the Civil Rights movement in general, and Birmingham, Alabama’s central role in it in particular.

“We’ve come a long way. A long way,” Tony said toward the end, shaking his head in remembrance. “But we still got a lot to do. We got to love people, and change people, and we got to know the history to know the truth.”

As we bid farewell to Tony, the words of Baldwin rattled in my head. In his 1962 A Letter to my Nephew, he wrote that many White Americans are “trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.”

As a family, we’ve always been committed to trying to understand our individual and collective histories, to face the past head on - even when painful, ugly, tragic, personal. To that end, we’ve taken our kids to war and genocide memorials in Bosnia and Herzegovina, read books about the Holocaust, shared photos and stories from Rwanda, and generally tried to be fully open, transparent, and honest about the past so as not to be trapped by it. To that end, we arrived in Birmingham ostensibly en route to the mind-numbing, bucolic beaches of Seaside, Florida, but with stops along the way in Alabama.

An hour later, our rental car rolled down the sun-baked, shimmering asphalt of Highway 65 toward Montgomery and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. It’s a site our kids (and Wende and I, too) long wanted to visit, to connect vacation with instruction, place with history and context and reality.

Set on six acres, the Memorial punches you in the heart with its simplicity: 805 hanging steel rectangles, each inscribed with the state and county in which one of the over 4,000 documented lynchings took place, and the names of the victims. The rectangles - shaped and sized like the coffins victims never received - begin at eye level; as you walk the labyrinthine testament to inhumanity, the ground drops and soon enough you’re looking upward, neck craning to the bottom of each rectangle, the resemblance to a corpse dangling from a tree unmistakable, striking, chilling, evoking countless lynching photographs like the one of Lige Daniels, murdered by a while mob on August 3, 1920, in Center, Texas.

…trapped in a history they do not understand…

Do not understand, or choose not to understand?

Walking through the Memorial, chilled to the bone despite the heat, it was easy to fall into the trap of disassociating oneself from the history. It was long ago. Ancient history. That time has passed.

But, it wasn’t. It hasn’t passed.

I remember James Byrd, Jr., chained by his ankles and dragged behind a truck for 3 miles by three white supremacists; I was 23. There was Mulugeta Seraw in Portland, Oregon, lynched in 1988; I was 14. Christopher Wilson was almost lynched in Florida when I was 20, and Yusef Hawkins was lynched in New York City when I was 15. And, Ahmaud Arbery was lynched on February 23, 2020, by three white men in Georgia; I was 46, and my children were 10 and 12. It’s not the past; it is our present.

…until they understand it, they cannot be released from it…

As I walked from the Memorial, my mind wandered to Helen, my late godmother, and her siblings. Helen knew her grandfather, Caesar McClellan, for 24 years before his death in 1944. Born in 1840, he was someone’s property for the first 25 years of his life. Helen died in 2015, having known well a relative who had no more rights than a suitcase for nearly 1/4 century.

How do we understand our history? What did Baldwin mean? I know well I’m not worthy of interpreting the meaning of thoughts from Baldwin, but I know this: We cannot understand. I cannot understand, truly understand, what makes a man drag another human to death, hang a girl from a tree, or claim ownership of a fellow human being. As Baldwin wrote: “One can be, indeed one must strive to become, tough and philosophical concerning destruction and death, for this is what most of mankind has been best at since we have heard of man. (But remember: most of mankind is not all of mankind.) But it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.”

But, I can - we can - cement the reality of our past, distant and recent, into the twisted mosaic of our present. Just because we cannot understand it does not mean we cannot embrace it, accept it as a tragic, awful, sinful part of our history, and by embracing it, by accepting it, by diving into it - painful as it is - we knowingly accept our lack of innocence, our unwilling complicity in the crimes of our past, and can begin to heal.

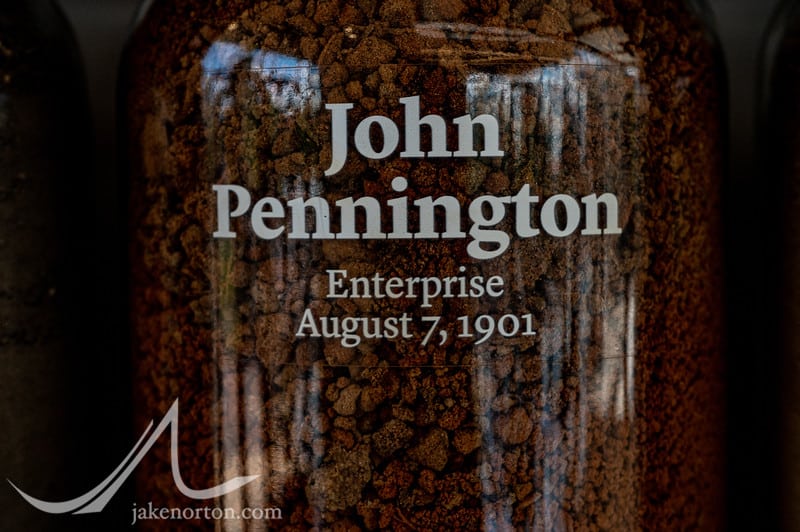

One of more than 360 jars that line the entryway of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Each jar memorializes one of the 4,743 lynchings documented between 1882 - 1968. Each jarm, labeled with the victim's name, date of death, and location, is filled with earth from the lynching site. A haunting a chilling memory of our past.

Quotation by Martin Luther King, Jr., in The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. It reads: "True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice."

Memorials at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

Memorials at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

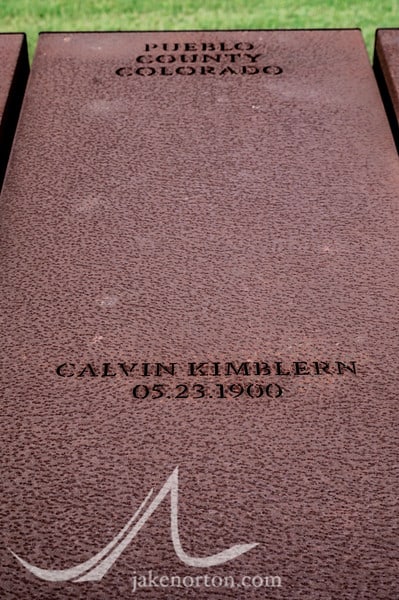

Memorial for Calvin Kimblern, lynched in Pueblo, Colorado, on May 23, 1900.

Plaque with quotation by Ida B. Wells at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. It reads: "Our country's national crime is lynching."

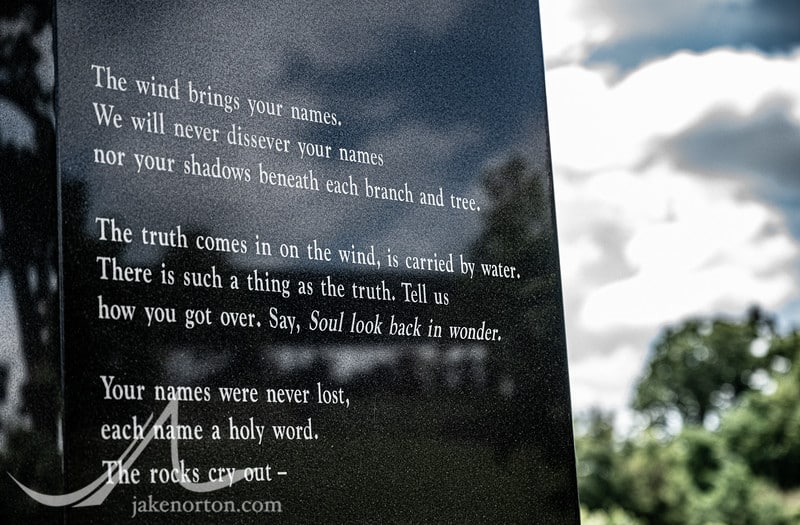

Segment of "Invocation" by Elizabeth Alexander at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

Baldwin ends his letter thus:

And if the word integration means anything, this is what it means: that we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it. For this is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what America must become. It will be hard, James, but you come from sturdy, peasant stock, men who picked cotton and dammed rivers and built railroads, and in the teeth of the most terrifying odds, achieved an unassailable and monumental dignity. You come from a long line of poets, some of the greatest poets since Homer. One of them said, The very time I thought I was lost, My dungeon shook and my chains fell off.

You know, and I know, that the country is celebrating one hundred years of freedom one hundred years too soon. We cannot be free until they are free.

James Baldwin, A Letter to my Nephew, 1962

Let us all shake the dungeon and release the chains that trap us in our history.

Jake,

Thank you for this heart- wrenching and activating piece. I recently finished 10 week course on racism, this is sacred ground. My ignorance overwhelmed me as I look back at our 400 years.

Silence is violence and I so appreciate your antidote to that violence as well.

Best regards,

Thank you, Steve. It is such a powerful place, well worth visiting and digesting, and uncovering the truths of our often obscured, hidden, lied about, dark past. And, thank you for being the light you are, a caring, compassionate person always eager to make positive change. I think back to our time in Mustang often...if not our scary flight out! Hope to see you soon!