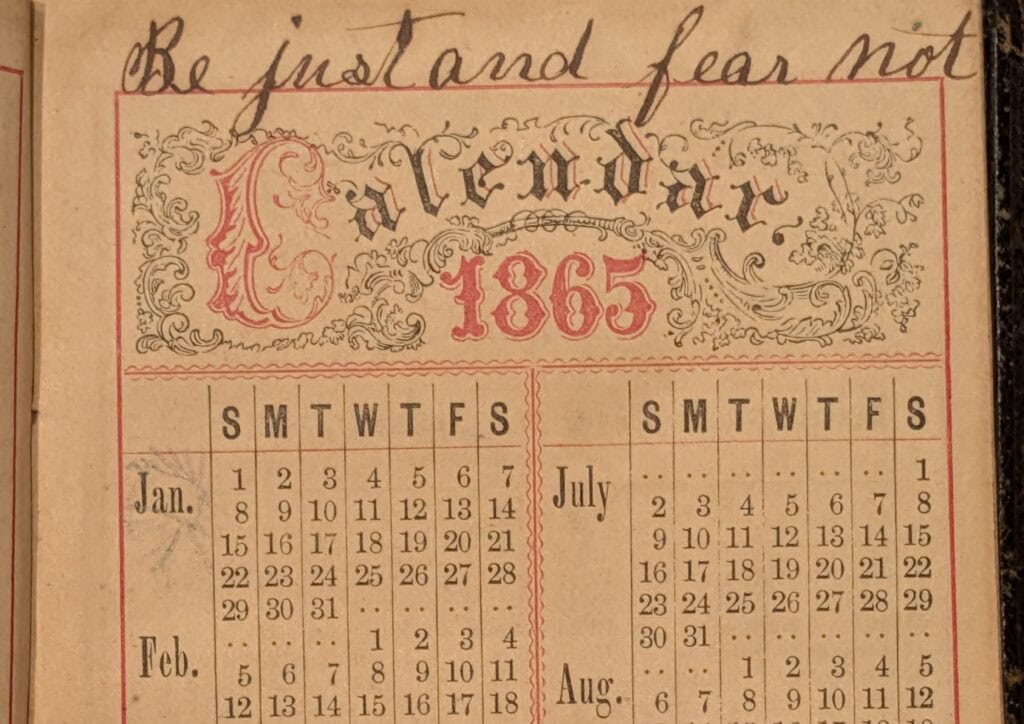

My paternal great-great grandfather, James T. Norton (1844-1883), was a man of few words. Or, at least that’s what his journal from 1865 indicates.

It’s been sitting near my desk for years. I’ve scanned the pages, faded scribbles in pencil recording minute datapoints about each day with little fanfare: weather, movement, rations, commands, engagements. Even having a rebel revolver placed to his head, being tied to a horse and then run fifteen miles into the woods, was cause for nothing but a factual recounting of events.

The journal notes that James’s wartime travels with Company E of the 10th Michigan Calvary took him through Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and on to Tennessee. I’ve been able to decipher little from the faded pages, but the start - January 1, 1865 - notes a cold, foggy morning with 5-6 inches of snow on Clinch Mountain, 1/4 loaf of bread to eat and some corn stolen from the horses, and the hope of “a happy year to come.”

But, it’s the frontspiece that is perhaps the most telling. There, in one of the only pages written in ink, are five simple words, meticulously written in delicate script: Be just and fear not.

I’ve often wondered what the common man, the regular soldier for the Union, thought about the war they were fighting, what they were fighting for. Abolition? The Union? Pay? Adventure? Perhaps a mix of all? It’s hard to tell, but James’s words at the front tell me a lot.

At about the same time, my maternal great-great-great grandfather, David Rhodes Sparks, was battling away for the Union in Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee as a Captain in the 3rd Illinois Cavalry. Not initially an Abolitionist, he was a fierce believer in the Union and, willing to lay down everything to preserve it, he enlisted in 1862. His experiences in the South and in the war, however, quickly changed his attitude. He wrote to his wife, Anna, from Batesville, Arkansas:

[W]hy do they [the Confederates] fight? I can see no reason except to gratify an aristocratic nature, the natural result of slavery, that "sacred institution." I have no doubt that some of my Southern sympathizing friends will be very ready to say that I have turned Abolitionist, a name they abhor, but let them leave their homes, as I have done, and ride through storm and snow, through rain and sun, and rest their weary limbs on the rough rocks of Missouri and Arkansas, with the cloudy or starry heavens for a roof and hard rocks for a bed and witness the blighting influences of the "institution" where persons with not more than one-quarter African blood in them are held in bondage, bought and sold like brutes - and then tell me if you think such practices consistent with a Democracy…

- Capt. David Rhodes Sparks, Batesville, Arkansas, May 9, 1862

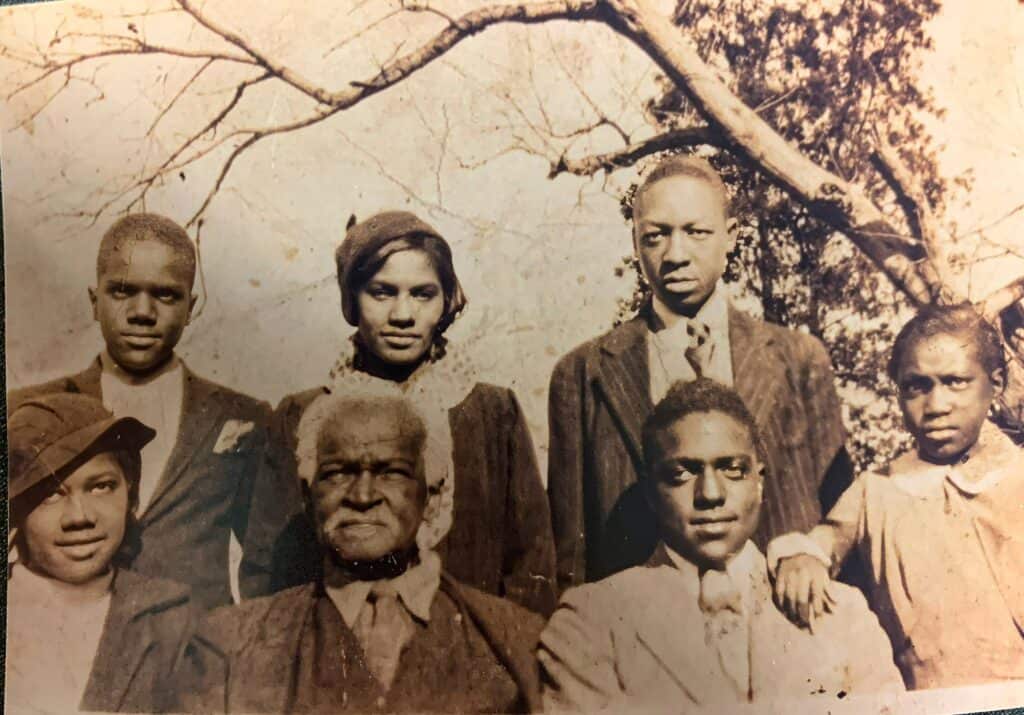

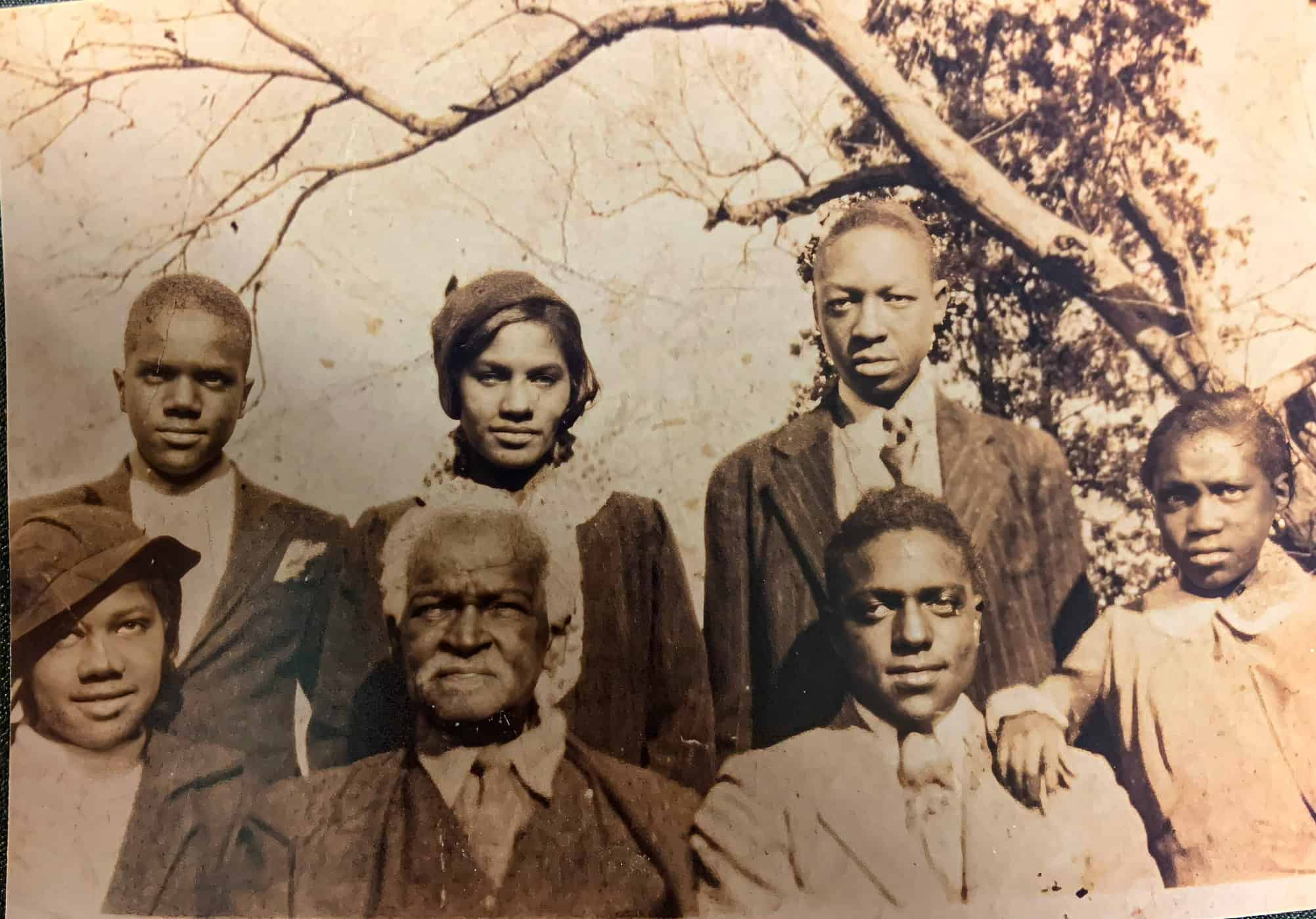

Simultaneously, another quasi-relative (of love, not of blood) was also in Tennessee. My godmother’s great-grandfather, Ceasar McClellan, was - like James T. Norton - in his early-20’s. Although I’m sure he wanted to fight, he likely didn’t, certainly couldn’t, because he wasn’t free: Ceasar was enslaved.

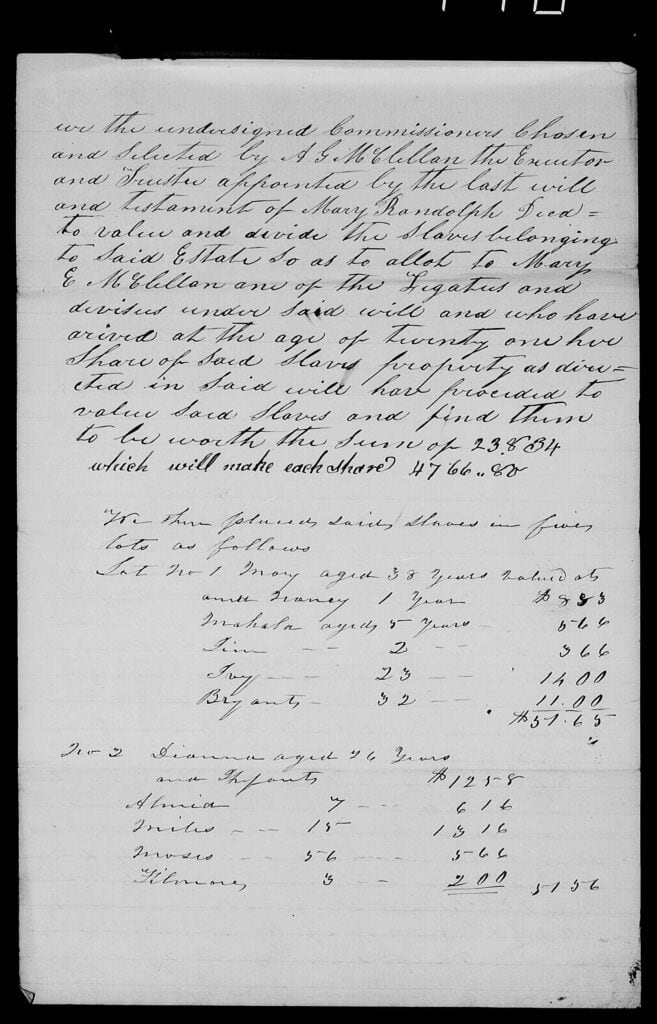

Born in Jackson, Tennessee, in 1840 or 1841, Ceasar was an involuntary part of that “sacred institution,” a man, a person, a human being reduced to an estate’s line-item by the abomination of American chattel slavery.

I’ve spent the past decade since my godmother, Helen Rhea, passed trying - mostly in vain - to research her family, to somehow pierce the paper curtain of 1865. The challenge 99% of the time is this: enslaved African Americans are, in individuality, all but invisible in the genealogical record prior to Emancipation. If enslaved, they could not own land, could not vote, were not listed (except in rare cases) by name on any documents - even slave schedules noted only sex and age and owner.

So, while I have rich records of James and David’s service in the Civil War, their thoughts as recorded on the battles and issues and outcomes of our nation’s greatest conflagration, nothing similar exists for Ceasar; it is quite like he - despite being 20 at the war’s outset - didn’t even exist. The few scraps I’ve been able to assemble are but hints:

- His mother, Jane Randolph, came likely from West Africa in the 1820s, a victim of the trade.

- According to Ceasar’s death certificate from 1944, his biological father was Perry Matthews. No other reference can be found.

- Jane at some point married Bryant Randolph, who was 32 in 1860 when he was given (along with 5 other enslaved individuals: May, Nancy, Mahala, Jim, and Jay) to Mary E. McClellan through the last will and testament of Mary Randolph, along with bundles of furniture, farm implements, livestock, and other items of the Randolph estate.

- Ceasar had six siblings, three of which - John, William, and Alic - were born enslaved, in 1849, 1852, and 1860, respectively. Thomas (1867), Jimmie (1868), and Silvie Ann (1874) were ostensibly born free, but the post-war South was not an easy place, nor a truly free one, for African Americans.

I’ve heard that Ceasar knew how to read and write, having taught himself the skills when no one else could or would. But, if he wrote anything down during those heated, chaotic days of the Civil War, as Union and Confederate forces traded occupation of Madison County and West Tennessee, I’ve been unable to find it. If he knew of, reacted to, Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, or Andrew Johnson’s freeing of his slaves eight months later on August 8th (Tennessee’s Emancipation Day), no record I know of exists.

But, I can imagine. I remember Helen - a woman of huge heart and few words - talking a bit about Ceasar, about him being a thoughtful, kind, generous, proud, perceptive, patriotic man. Helen’s sister, Icy (amazing woman and author of God Don’t Make Oops), said the same, as have other family members. So, I can imagine the joy that Ceasar felt when emancipation finally arrived - emancipation not in thought or on paper, not whistled in the wind and whispered in the shadows - but true emancipation in its essential, physical form.

Joy. Joy shared by Jane and Bryant and all the other enslaved people in Jackson, Tennessee, and in Galveston, Texas, and throughout the United States of America. The joy of freedom, the joy of a nation finally, painfully, living into its values, its fundamental principles long written and now slowly, possibly coming to realization. The joy of a bitter and costly war coming to an end, people like James and David who sacrificed much coming home knowing that sacrifice was not in vain. The joy of at least half a country - white, black, and brown - that had struggled and suffered, battled and bled, fought and ultimately prevailed, for something greater than themselves, serving more than themselves.

And that is what makes Juneteenth1 so important, so worthy of recognition, celebration: it is a moment in time when we - as a nation, as a people, as a collective - were not great; far from it. But, we were, individually and collectively, as a nation, not arriving at, but moving toward, greatness. Progressing. Living out our values of justice and equality for all, marching fearlessly into the light of a new day, of new possibility.

Was America great then, on June 19, 1865? Not even close. We’d closed the gap, moved toward the goal, but still had a long, long way to go. Are we great now? Closer, but still not there, the goalposts fuzzy on the distant horizon. Much work to do, progress to be made.

And maybe that’s the point: like shadows in Plato’s cave, greatness is something we aim toward, but never arrive at. The journey takes courage, faith, and determination, the resilience to carry on, the bravery to admit shortcomings and failings. We may never be great, but we can forever work to be so.

Be just and fear not.

When day comes we step out of the shade

- Amanda Gorman -

Aflame and unafraid

The new dawn blooms as we free it

For there is always light

If only we're brave enough to see it

If only we're brave enough to be it.

- I can’t say that I was surprised when yesterday, June 19, 2025, the 160th anniversary of Juneteenth was marked by President Trump with…crickets. Nothing. No celebration, no mention, no acknowledgment, not a word. (Not even an all-caps social media post. I’m not really surprised, but maybe a little since he made a big deal about it when, in 2020, he first became aware of the day thanks to a black Secret Service agent, but later took undue credit stating: “I did something good: I made Juneteenth very famous. It’s actually an important event, an important time. But nobody had ever heard of it.”) ↩︎

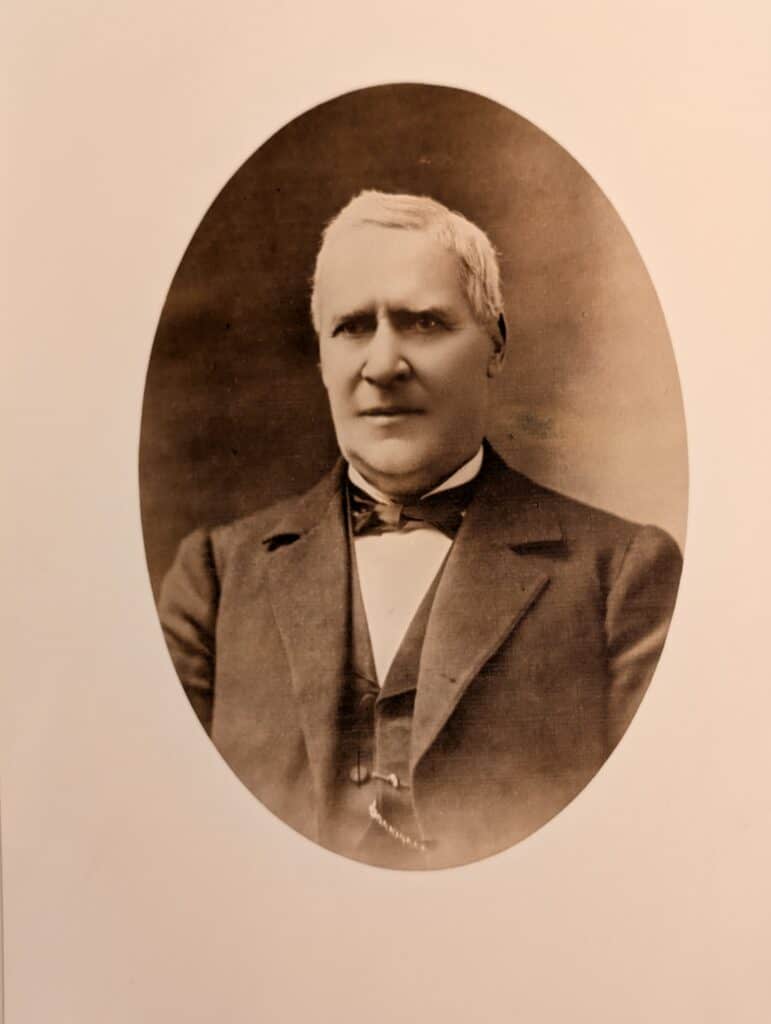

Thanks Jake for all you do to keep our family history alive.The person on the left is Dorthy Davidson Helen's first cousin.

Dear Nathan, thanks for your comment and note, and so so sorry to have missed it. And, thank you for the ID on the photo - I'll add that to my notes!

Sending you and Pearl lots of love, and hoping that all is well with you both! And, hoping to see you again sometime sooner than later! Love, Jake

Interesting story and history - and important, I’m intrigued.

The quote - I love it - simple words, yet huge and powerful when put together. ”Be just and fear not”. The strongest word and the power lies in the ”and” I believe, surprisingly.

My daughter graduated last week and it has made me reflect on life, trying to pass on words of wisdom to her. The speach is held, the party is over but I’ll pass this quote on to her (and her brother). It is such an empowering buton - a strong ”one-liner”.

So thank you for sharing your story.

Thank you, Lotta, truly appreciated! And, congrats on your daughter's graduation!

Jake. Incredible in all ways. Your research, your reflection, your thoughtful articulation. Amanda Gorman is the icing. Thank you for opening the door and allowing us to reflect alongside you. Be just and fear not. With appreciation, Caroline Fisher

Thank you, Caroline! Coming from you this means a ton! Sending you all the best, and hope to see you soon.