The wildness of the place was like nothing I had experienced before. Vast expanses of nothing spread out all around me - nothing, that is, as opposite to the human colloquialism and definition of “something.” There was no shopping center or mini-mall to be seen, not a house or a road or a toilet or even much of a trail beyond the simple, subtle path created by prior feet and prior experience.

But, beyond all that nothingness, within the void of human impact there was certainly a lot of something, a profound something that enchanted me, touched me, moved me, inspired and enriched me. The Wind River Range in 1988 was as deep into the corners of the map I had ever been, a journey into the wilderness as foreign to my experience in growing up in New England as the moon, and it was life changing.

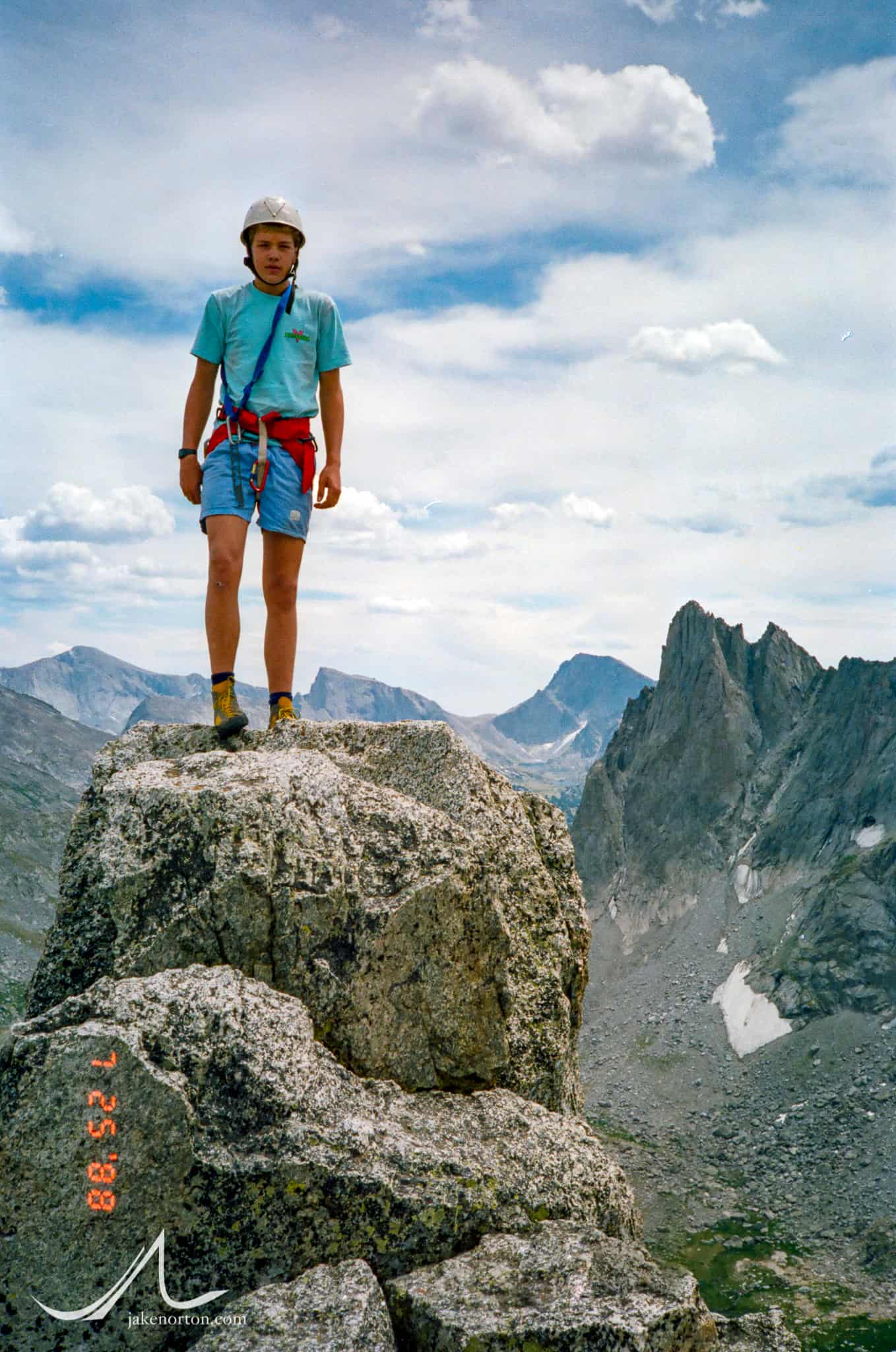

For ten days, I climbed sweeping towers, 1,000+ foot sweeping walls of granite punctuating the rim of the Cirque of the Towers, making it look like the ancient maw of the universe. It was just me, age 14, with a guide, Dave Colke, who I had just met. I was a shy kid (who would grow into an introverted adult), and Dave was a man of few words, so conversation amounted to little more than instruction on technique, direction on route, and maybe a few words about weather and location and history at dinner over the muted roar of the stove. While admittedly awkward at times, it was also sheer bliss: we climbed 9 long, alpine routes over 8 days in the Cirque, rinsed under cascades of the upper Popo Agie coursing down smooth-worn, granite slabs, slept on rock under impossible, starry skies, caught sunrises from high belays, and saw only 2 other people (fishermen, not climbers) the entire time.

That trip more than any other opened my eyes to the experience of true wilderness, naked wildness of the natural world unsullied and tainted by the order-seeking hand of humans. Deep in the nothingness of the Winds, Dave and I (me for the first time, he for the zillionth) experienced the unpredictability of nature, from storms sweeping unannounced over the spires of the Watchtowers to rocks loosed from above by unseen forces, hurtling downward with wanton abandon. We, too, engaged the unpredictability of humans in a challenging realm: While on the classic East Ridge of Wolf’s Head, the rope jammed fast in the hand crack traverse of Pitch 4. I, a very green and inexperienced climber, had to pull in slack, re-tie into the rope, cut the jammed part, and continue climbing the rest of the pitch, all with minimal-to-no communication. The next day, our ropes got abysmally stuck on rappel from the summit Shark’s Nose, forcing Dave to free-solo back upward to free them while I waited alone, contemplating all the while what I might do should Dave not return from his mission. And, off the towers, we were forced to engage one another, two laconic introverts - one an East Coast liberal, the other a Wyoming-born conservative - learning to converse; by the walk out on day ten, we were laughing and sharing stories for hours on end, our introversion and difference muted by common experience.

The wilderness - be it land designated as such or simply those places far from the human-drawn realm - has long inspired humans in myriad ways, this one very much included. The power of it, though, far transcends mere inspiration by landscape, the throbbing heart brought on by sublime beauty. That power of the wild is important for certain: the sheer magnitude of wilderness induces in us a liberating humility, an overwhelming conception of our innately minuscule presence in nature.

But, wilderness - and our experience in it - has far more to offer than artistic or theological inspiration. Wilderness is wildness inherent; it is unpredictable, at least in relation to our coded and codified sense of prediction. Thing happen in the wild that are not expected, cannot be predicted, and challenge our very beings as a result. Be it the storm sweeping in and covering Block Tower in a glaze of ice, or the trust one learns to place in another flawed human to ensure survival, we experience in the wilderness a wildness we conveniently avoid in society…a wildness that conjures fear, anxiety, avoidance simply for its unpredictability, its deviation from the norm. We are drawn to simplicity and predictability, and have built our society to ensure that; as I’ve shared before, Rebecca Solnit put it well:

The industrialized world has tried to approximate paradise in its suburbs, with luxe, calme, volupté, cul-de-sacs, cable television and two-car garages, and it has produced a soft ennui that shades over into despair and a decay of the soul suggesting that Paradise is already a gulag. Perhaps that paradise is indeed a gulag, a prison of sorts, one whose organization and comfort and utter predictability renders us unable (or unwilling) to engage with the wild of humanity, the difference that is humanity, but from which we build and organize and stratify in a desperate and futile attempt to hide from.

- Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities

No, experience in the wilderness has much to teach us all. In it we learn to tolerate the unpredictable, perhaps even embrace it, and see it as a means of building, growing, expanding, learning. Life in the wild teaches us - forces us - to accept the unknown as part-and-parcel of existence, and through it we learn to live with and adapt to a changing landscape. Likewise, wilderness life allows us to work together as humans, to be more accepting of diversity in all its forms and manifestations: when you’re immersed in the wild, backed up against the fundamentals of life rather than the numbing comforts of modernity, you learn quickly to trust one another, to have faith in fellow humans despite your differences (or perhaps because of them). The field is leveled, the wildness exposed, connection enabled by unavoidability.

Years later, in Colorado, I came upon a hermit living in a lean-to in the woods deep in the southwestern ramparts of Pike’s Peak. He was there alone, as he had been he told me for more than a decade. “Escaping the humans,” he told me. “This is where life really is. It’s not out there, it’s here, away from it all.” Perhaps so - I was certainly not in a mood to argue with him, holding as he was a loaded shotgun. But, it always struck me as far too binary, too black and white, too simplistic, and too much avoidance and escapism. I felt (and feel) that what the wild taught me was a lesson about how to engage with, and hopefully improve, the world of humans, not escape them.

Days after our time in the Winds, I was in Jackson Hole, waiting to a try at the Grand Teton, and came upon the writings of Willi Unsoeld. The grandfather of experiential education, Unsoeld was a Director of the Peace Corps - Nepal, founding faculty of Evergreen State College and Outward Bound, first to climb (along with Tom Hornbein) the West Ridge of Everest, and a whirling dervish of thought and risk and energy and philosophy. In his own, eccentric, Willi way, he summed up this wilderness experience, what it means, and why it is so essential, now more than ever:

And so what is the final test of the efficacy of this wilderness experience we've just been through together? Because having been there, in the mountains, alone, in the midst of solitude, and this feeling, this mystical feeling if you will, of the ultimacy of joy and whatever there is. The question is, "Why not stay out there in the wilderness the rest of your days and just live in the lap of Satori or whatever you want to call it?" And the answer, my answer to that is, "Because that's not where people are." And the final test for me of the legitimacy of the experience is, "How well does your experience of the sacred in nature enable you to cope more effectively with the problems of mankind when you come back to the city?"

And now you see how this phases with the role of wilderness. It's a renewal exercise and as I visualize it, it leads to a process of alternation. You go to nature for your metaphysical fix - your reassurance that there's something behind it all and it's good. You come back to where people are, to where people are messing things up, because people tend to, and you come back with a new ability to relate to your fellow souls and to help your fellow souls relate to each other.

- Willi Unsoeld

Thanks Jake. Wind River is my wife’s oncologists favorite place in US - I must go. Steve

Thanks, Steve! It is such a magical place, and well worth the visit even if it's busier now than when I was there. I hope you're well, my friend, and hope we can get out on another adventure sometime!

All my best,

Jake