Climbing books — especially those focusing on extraordinary ascents and massive achievements — are rarely tomes of humility, tending instead to hubristic celebrations of one’s strength, power, and ability. As a kid, when I began reading these books, it was something that always turned me off, repulsed me to some degree, for it seemed to cheapen the experience I perceived in climbing, a deeply profound experience of unimaginable beauty born of humility, of a landscape and activity solidifying in no uncertain terms that we are but mere participants in the game at hand, the game of life, and our success or failure means little aside from the recognition of the need to forever strive forward, onward, upward, with grace and love and a sense of wonder.

I was thrilled when, in 1986, my great uncle passed along to me a tattered, dogeared paperback of a book called simply “Everest: The West Ridge.” For inside those worn pages was the story of courage and determination, teamwork and camaraderie, philosophical inquiry amongst massive-but-humble success. One needs only to browse quickly through the book to be intrigued; not many climbing books include quotes from a UN Secretary-General, and especially not ones like this from Dag Hammarskjöld, printed on the final page:

Never let success hide its emptiness from you, achievement its nothingness, toil its desolation. And so keep alive the incentive to push on further, that pain in the soul which drives us beyond ourselves.

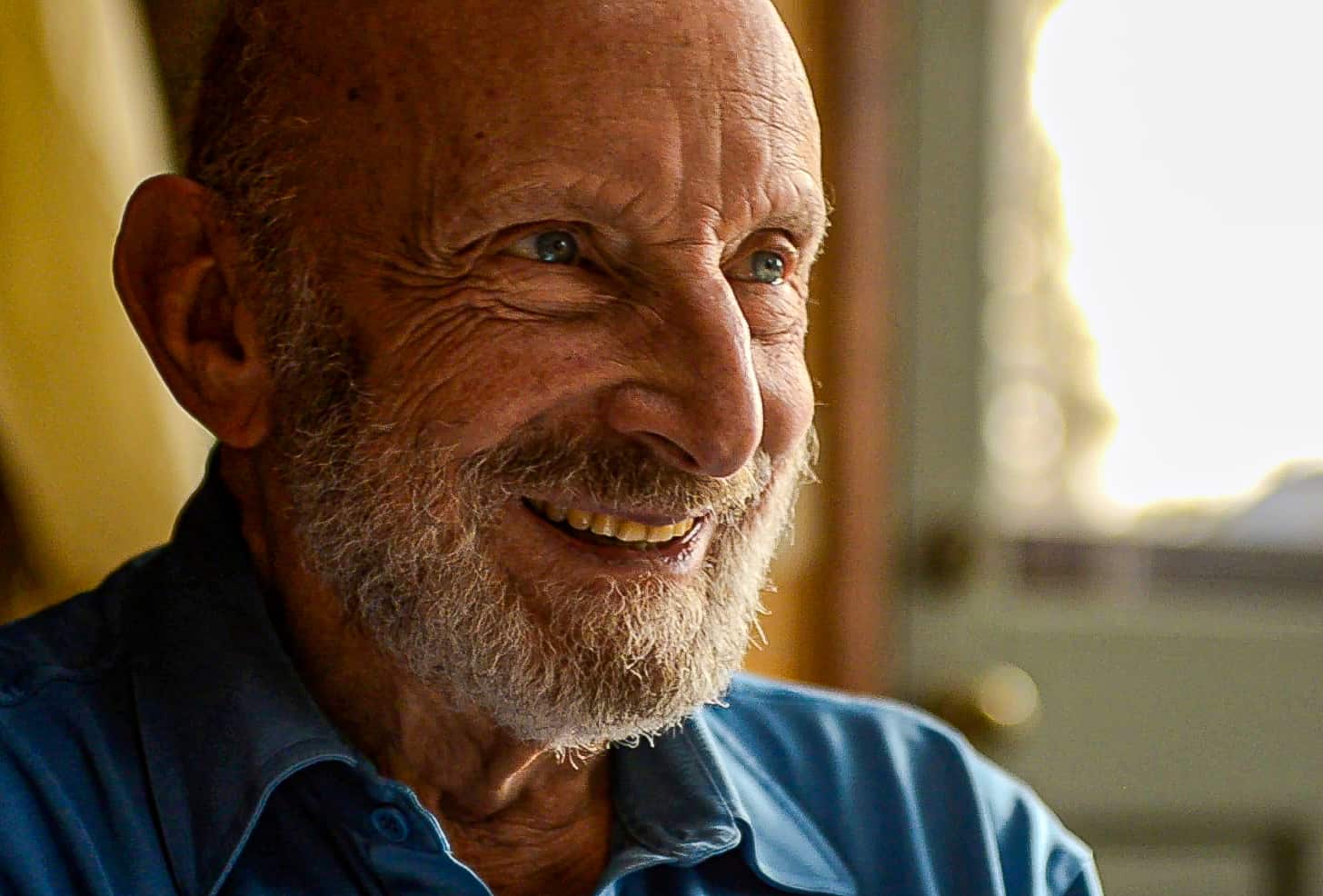

But, thankfully, such is the personality and disposition of Tom Hornbein, who turns 90 today. I’ve been fortunate enough to get to know Tom over the past 15 years, working with him on a film about the 1963 West Ridge climb, sharing stories and philosophies, and learning more from him about life and its meaning than he’d believe.

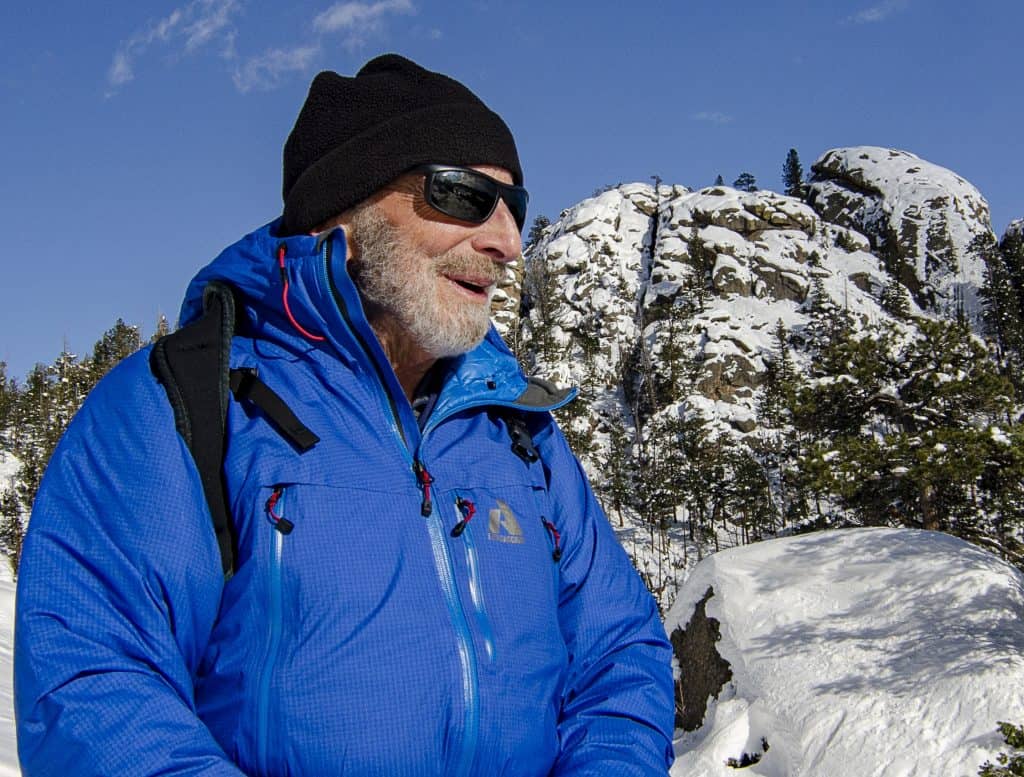

Perhaps the most amazing thing about Tom is that he never let his life be defined by Everest. While he and Willi Unsoeld pulled off a climb of historic proportions and ushered in a new era of possibility in the high Himalaya, it never got to Tom’s head. A successful anesthesiologist, he refused to become “the Doc who climbed Everest,” focusing instead on being simply the best doctor, professor, innovator, friend, and person he could; Everest was (and is) but one arrow in his overflowing quiver.

I was on a Zoom the other night with some 30 people, all gathered to celebrate Tom’s 90 years in the 2020 COVID-19 way. The organizer of the gathering, Harry Kent, summed up the evening best when he said: “Tom, it’s amazing to me as I gaze out at the eclectic community that’s gathered here for you, people from all over, climbers and doctors and teachers and writers and philanthropists. We’re here to celebrate you, to give you a gift, and through your life and the people you connect, you’re giving US the greatest gift, one of inspiration and connection.” Tom, in usual fashion, gave a quick thanks and quickly redirected the conversation away from him and back to the people gathered. True and beautiful humility.

There’s so much more I could say about Tom; 90 years packs in a lot. But, instead, I’ll let him give a taste of his way of seeing the world. In 2012, when making our film, we had Tom read some favorite passages from his book. I believe they capture much of the essence of Tom as a climber, as a doctor, as a husband and father, as a person and friend and mentor; read below, or listen to Tom reading aloud in the video.

Happy Birthday, Tom. Here’s to you, and to many more birthdays yet to come.

The flag left there [on the summit] seemed a feeble gesture of man that had no purpose but to accentuate the isolation. The two of us who had dreamed months before of sharing this moment were linked by a thin line of rope, joined in the intensity of companionship…We felt the lonely beauty of the evening, the immense roaring silence of the wind, the tenuousness of our tie to all below. There was a hint of fear, not for our lives, but of a vast unknown which pressed in upon us. A fleeting feeling of disappointment- that after all those dreams and questions this was only a mountain top-gave way to the suspicion that maybe there was something more, something beyond the three-dimensional form of the moment. If only it could be perceived…It is this simplicity that strips the veneer off civilization and makes that which is meaningful easier to come by-the the pleasure of deep companionship, moments of uninhibited inhibited humour, the tasting of hardship, sorrow, beauty, joy. But it is this very simplicity that may prevent finding answers to the questions I had asked as we approached the mountain…It is strange how when a dream is fulfilled there is little left but doubt.

— Tom Hornbein, Everest: The West Ridge