Note: In 2013, Pete McBride, David Morton, and I followed the Ganges River from source to sea. To learn more about this adventure and about the Ganges, read my post Ganges - Source to Sea or watch the film Pete and I made - Holy (un)Holy River - on Amazon Prime or Vimeo on Demand. Subscribers to jakenorton.com can watch for free.

King Bhagirathi had a problem. Some 60,000 of his countrymen had been killed by the demonic gaze of the sage Kapil, and without purifying waters flowing on earth, their souls were trapped, wandering aimlessly, unable to attain moksha, or salvation. Desperate, Bhagirathi appealed to Brahma, the God of Creation, for help. Brahma said he could help by bringing his daughter, the goddess Ganga, to earth…but only after sufficient devotional acts. Bhagirathi agreed and commenced 1,000 years of devout prayer and penance - now known as Bhagirathi Prayatna - an act of great effort, and great achievement.

Good to his word, Brahma released Ganga in her liquid form, ordering her to descend to earth. Not one for being bossed around, however, Ganga grew angry and decided to enact her wrath in a destructive fall from the heavens, intent on obliterating the ground where she fell. Sympathetic to Bhagirathi and the plight of humanity below, Shiva intervened by laying out his thick dreadlocks and breaking Ganga’s fall, slowing her destructive power; from his hair she flowed freely from the mountains to the sea.

“These days, She is angry,” Muni Baba jotted in a tattered notebook for us to read. We sat on the floor of his tiny stone hut, sipping hot chai. “She is peace, but She is also power. People are hurting Her, abusing Her, and She will not stand for it.”

An energetic man with twinkling, engaging, wizened eyes, Muni Baba has not spoken in more than a decade. A vow of complete silence is his chosen penance, his mode of asceticism to bring him closer to the divine. Perhaps to make the vow easier to maintain, he’s lived most of those years in this small hut on the edge of the meadows at Tapovan, a tiny dot astride the Gangotri Glacier’s western moraine, sandwiched between the sweeping massifs of Shivling and the Bhagirathis.

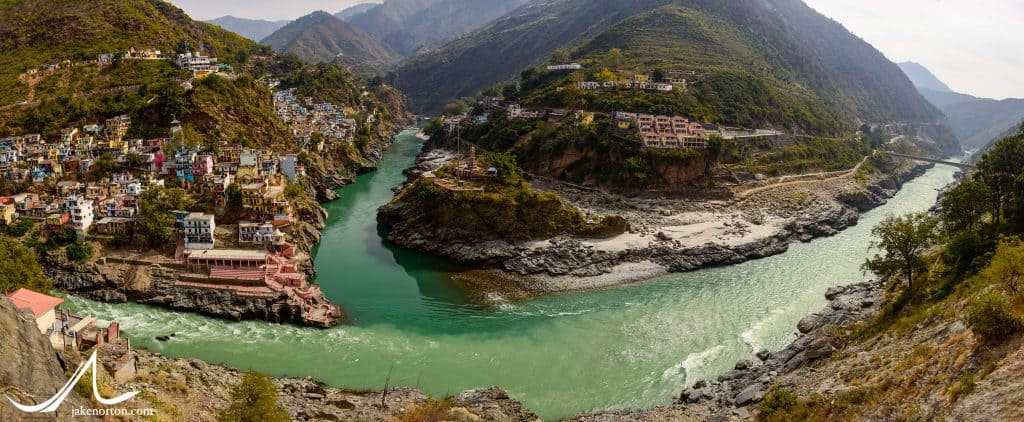

The She of which he spoke is Ganga, the divine incarnation that begins her earthly run as a trickle beneath our feet, gaining meltwater and power until bursting forth furiously from the toe of the Gangotri Glacier at Gaumukh, or “Cow’s Mouth,” a few hours downstream. From there, the Bhagirathi - as it’s known in the high country - flows through canyons carved by eons of water before joining with the Alaknanda miles downstream at Devprayag and becoming the Ganges - lifeblood of India, providing daily physical nourishment to several hundred million and spiritual salvation to some one billion Hindus.

But, before the Ganges is officially born - when she is still the Bhagirathi, above the confluence - she already endures the stain of humanity, the taint of those who she was sent to save. In our water tests of fresh snow falling upon the glacier at 17,000 feet, many miles above Tapovan, we found heavy metals and other contaminants already present, airborne pollutants sullying a seemingly pristine landscape.

Not far below, her waters flow strongly atop the Gangotri, supra-glacial streams that should be flowing under and within the glacier. Instead, thanks in large part to warming temperatures, they’re coursing on top, waters carving channels in a glacier that is one of the biggest in the Himalaya. At 30.2 kilometers long, it contains an estimated 27 cubic kilometers of ice, but it’s retreating rapidly: Of the 1223 meters (4012 feet) of recession from 1936-1999, 926 meters (3038 feet) of that occurred 1975-1999. Another 150 meters (492 feet) were lost from 2010-2016.

Below Gaumukh, the Bhagirathi flows relatively unhindered for miles but eventually meets with more human intervention, most notably at the massive Tehri Dam - India’s largest and perhaps most controversial. At 260 meters (855 feet) high and 575 meters (1886 feet) wide, the mega-dam cost $2.5 billion to build, holds back some 3,200,000 acre feet of water, and produces 1,000 megawatts of electricity. Sitting in a major seismic zone capable of producing massive earthquakes, the dam’s geologic stability - and the devastating downstream consequences of its failure - is worrisome to many. The region is also ecologically critical and highly sensitive, with long-term impacts caused by diminished post-Tehri flows of the Bhagirathi as yet unknown. (Since 2005, outflows have reduced from the normal 1,000 cubic feet per second to only 200.) Nearly 100,000 people were moved to build the dam and reservoir, many of them unwillingly, leading to protracted legal issues and protests.

“Maa Ganga has great power,” another ascetic told me down valley in the pilgrim village of Chirbasa. “She is gentle, but look what She does when we make Her angry!” He gestured down valley, a look of fright etched across his brow. Just weeks before our arrival, the region was hit by a horrific flooding event known as the Himalayan Tsunami, which tore down valleys, destroyed villages, forced the evacuation and rescue of 110,000 people, and killed at least 5,700. Some, including my friend in Chirbasa, believed it was a clear sign of Maa Ganga’s fury at the misdeeds of mankind: Why else would the sacred Shiva temple of Kedarnath be saved by a massive boulder when all around it was destroyed?

A sign from Ganga or not, the 2013 floods did little to check the changes and development along the great River. Despite being elected on a campaign of cleaning the Ganges, Narendra Modi’s administration has done little to help the river, and a lot to challenge it, including eliminating wildlife sanctuaries to allow dredging the river for an inland waterway, standing by while pollution levels climb to record levels, and continuing development of contested hydro projects along the river. In 2018, G.D. Agrawal - a retired engineer and ardent activist for the Ganges - began a new fast in protest of the Modi administration’s treatment of the river, with specific attention on the hydro development in its upper catchment areas along the Bhagirathi and Alaknanda. Modi received his letters of complaint, but they went unanswered; Agrawal died in hospital on October 11, 2018, after 111 days of fasting.

The Ganges flows on, but not happily. Many believe her wrath, long ago quelled by Shiva and his hair, is rising once again. Just days ago, a chunk of the Nanda Devi Glacier collapsed, releasing a demonic torrent of water and ice which roared down the Dhauliganga and Alaknanda Rivers, destroying two hydro plants and killing at least 31, with another 165 missing. The search for survivors continues, and the event is likely climate related.

In Rishikesh, the story of Bhagirathi’s penance and salvation was told to me by another spiritual devotee of Ganga. We sat on Ganga’s banks, her placid waters gently coursing over the broken cement where her fury toppled a massive Shiva stature weeks before. “Ganga is everything to us, to India. Without Her, we have no history, and no future. Nehru said that, and it is true. We need strength to save Her, and we must.”

It is time for another Bhagirathi Prayatna, this time not to save the souls of humanity, but to save the soul of a nation and the divine river which has given India so much, for so long.

Intresting,insightful and thought provoking essay.

Thankyou for compiling it.

Thank you, Himanshi. Be well!