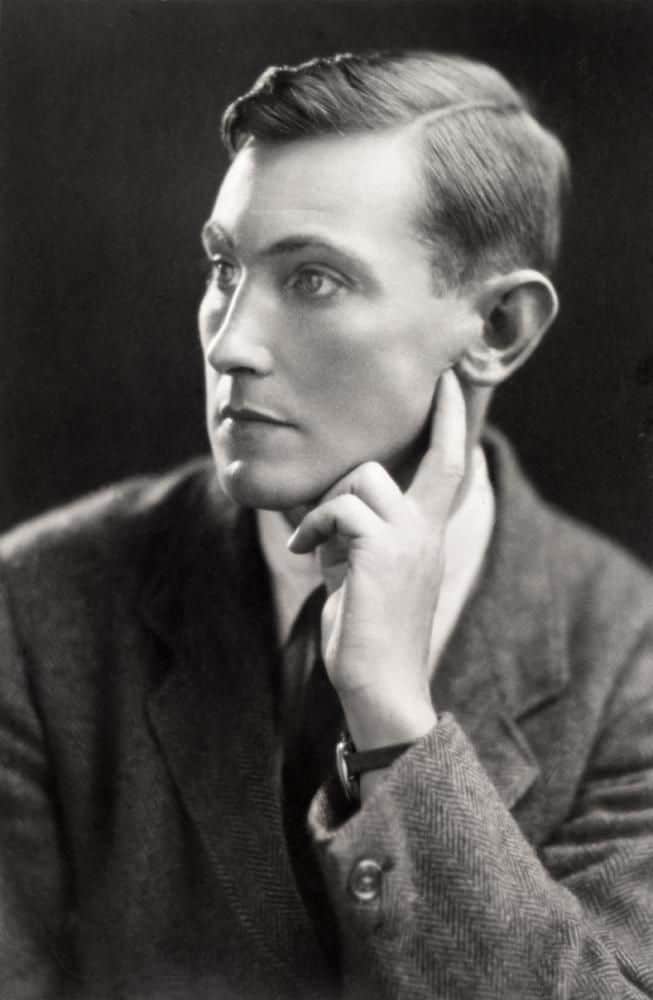

George Mallory is known for his climbing, or, more specifically, for his disappearance climbing.

And, of course, he's known for his famous quip in 1923: Because it's there.

But, rarely written about are Mallory's more philosophical works and thoughts, of which there are many. And, one of my favorites is the subject of today's Thursday Thought.

In 1914, ten years before his death on Everest, Mallory wrote a piece in The Climbers' Club Journal entitled "The Mountaineer as Artist". Mallory perhaps overstretches at times while trying to tie mountaineering to a symphony. But, at its core, "The Mountaineer as Artist" strikes a chord (no pun intended) with the sublime experience of mountaineering.

I will only share a portion of his thoughts here. If you want to read the full

piece, pick up a copy of the classic The Armchair Mountaineer for this an many other great writings on climbing, or for a deep dive on Mallory and his writing, get Peter Gillman's comprehensive Climbing Everest: The Complete Writings of George Mallory.

But, back to our Thursday Thought.

What is the essence of climbing? What makes it valid…and valid enough for many to risk life and limb pursuing it?

And, why is it so difficult for climbers to describe the sublime rewards of the mountain environment?

Here are some of Mallory's thoughts:

Climbers…like myself…have much to explain, and it is time they set about it. Notoriously they endanger their lives. With what object? If only for some physical pleasure, to enjoy certain movements of the body and to experience the zest of emulation, then it is not worthwhile. Climbers are only a particularly foolish set of desperadoes…The only defense for mountaineering puts it on a higher plane than mere physical sensation. It is asserted that the climber experiences higher emotions; he gets some good for his soul. His opponent may well feel skeptical about this argument. He, too, may claim to consider his soul's good when he can take a holiday. Probably it is true of anyone who spends a well-earned fortnight in healthy enjoyment at the seaside that he comes back a better, that is to say, a more virtuous man than he went. How are the climber's joys worth more than the seaside? What are these higher emotions to which he refers so elusively? And if they really are so valuable, is there no safer way of reaching them? Do mountaineers consider these questions and answer them again and again from fresh experience, or are they content with some magic certainty born of comparative ignorance long ago?

We do not think that our aesthetic experiences of sunrises and sunsets and clouds and thunder are supremely important facts in mountaineering, but rather that they cannot thus be separated and cataloged and described individually as experiences at all. They are not incidental in mountaineering but a vital and inseparable part of it; they are not ornamental but structural; they are not various items causing emotion but parts of an emotional whole; they are the crystal pools perhaps, but they owe their life to a continuous stream…

- from "The Mountaineer as Artist," by George Mallory, 1913