I came across this wonderful image from a 1933 advertisement for a new windsuit to be used on Mount Everest for the 1933 Everest Expedition. It originally appeared in the March, 1933 edition of Popular Science magazine. Seems that climbing equipment was making great strides back in the early 1930’s – while it may look primitive, it was a big jump from the Gabardine, wool, and tweed used by George Mallory and Andrew Irvine on their fateful ascent in 1924.

The 1933 attempt on Everest was the fourth attempt by the British since the 1921 Reconnaissance Expedition, and the first in 9 years after the tragic deaths of Mallory & Irvine on June 8, 1924.

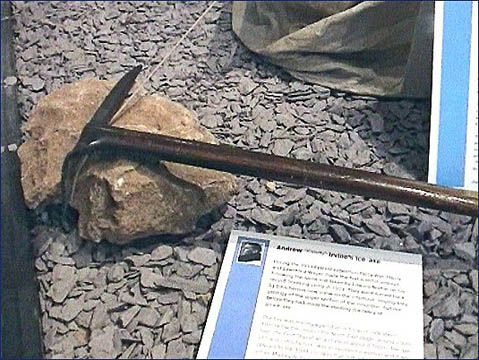

While the 1933 expedition did not reach the summit of Everest, they did manage to climb high on the mountain. On May 30, 1933, climber Percy Wyn-Harris – attempting to summit with Lawrence Wager – stopped at about 27,600 feet, just below the First Step on the Northeast Ridge, and noticed something wooden sticking out of the rock…Curious, he went down to investigate, and found an ice ax laying on the rocks. No one else had been there but Mallory & Irvine, 9 years before. It had to be one of their axes. Wyn-Harris picked it up, leaving his in its place, and later at Basecamp the ax was identified as Andrew Irvine’s.

Sixty-eight years later, in 2001, I was able to retrace Wyn-Harris and Wager’s footsteps on the Northeast Ridge with my friend Brent Okita as part of the 2001 Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition. In my May 5 dispatch that year, I wrote about our trip the week before: hunting for the ice ax location, looking for evidence of Mallory & Irvine, and finding some amazing artifacts from the 1933 expedition.

Essay: 68 Year Old Crackers

Jake Norton – Basecamp

Sat, May 05, 2001 2:00AM

I tripped over it. I wish I could say it was different; I wish I could

with good conscience tell the world how my skill and detective work led

me to the 1933 Camp VI in 1999. But… no such luck. A bit of the pack

frame seemingly jumped out of the snow beneath my feet and nearly threw

me on my face. There you have it.

This year, however, the same was not going to happen to me. When Brent

Okita and I set off on April 29th to fix line through the Yellow Band

and onto the Northeast Ridge, I was determined to find the camp without

it finding me first. I remembered with longing the last time I laid

eyes on it: It was about 8:00PM on May 17th, 1999, and Tap and I were

in the Yellow Band again to lend a hand to a tired Conrad Anker and

Dave Hahn as they returned from their summit day. I had already pulled

out the toe-tangling pack frame earlier in the day and carted it back

to Camp VI. Now, in darkness broken by my headlamp beam, I could make

out the tatters of a couple brown, down sleeping bags and bits of paper

and tin. But, it was not the time for excavation, and I forced myself

to put it off till another time.

On April 29th, Brent and I fixed fresh line through the Yellow Band and

up to the Northeast Ridge. Our goal was twofold: prepare the route for

upcoming summit bids while also searching for artifacts high on the

mountain. A few hours of pounding pitons and tying knots led us to the

crest of the Northeast Ridge. Knowing that the top of these gullies can

be difficult to find at times, I began looking around for something

with which to mark the route. A bit of brown cloth protruded from a

snowy hole at my feet; looking closer, I pulled an old, felt mitten

from the slope. Immediately, I could feel a tiny burst of adrenaline,

the spark of excitement from finding and touching an item from Mallory

and Irvine’s day. I tucked it into my down suit for safekeeping and

kept on moving.

Soon, I was scrambling along the crest of the ridge, being constantly

wary of the silent killers to my left: huge cornices overhang the great

Kangshung (East) Face of Everest… Get too close, and you will pop

through their fragile, snowy veneer and take a 10,000 foot sled ride

down below. Trying my best to ignore that unpleasant reality to my

left, I gazed about looking for more evidence of the climbers of old.

Ahead, a familiar object: a long, ribbed oxygen bottle with bright blue

paint. I knew this well from 1999 as a 1975 Chinese O2 cylinder. Others

lay nearby. I radioed down to Jochen at Basecamp, and he mentioned that

I could be near the sight of the 1975 Chinese Camp VII (which was later

used by the American Ultima-Thule 1984 Expedition). Sure enough, just

on the crest of the ridge in a small snow-and-rock dish lay a tent with

thick, old-school aluminum poles and several more blue oxygen

cylinders. The Chinese were certainly here in ’75. I moved along.

Before long we came to another point of historical significance: the

spot where Percy Wyn-Harris left his ice axe in 1933 in place of Andrew

Irvine’s which he had just found. Scouring the slabs of the Yellow

Band, Brent and I longed to see some bit of wood in the limestone

rubble. Unfortunately, it seems the ’33 ice axe has been washed off the

slabs by a rockslide or avalanche in the 68 intervening years.

Nonetheless, wandering the limestone sidewalks of the Yellow Band

allowed me to do some historical investigation. Gazing downward, I

could see the basin in which we found Mallory in 1999; certainly, it

lies in a natural fall line from the ice axe. But, a hitch: There is

absolutely no way that the ice axe could mark the site of the fall

which led eventually to Mallory (and presumably Irvine’s) death.

Looking to the basin below, it became obvious that a fall to the basin

below would not only be unconditionally fatal, but would be completely

body-shattering as well. Mallory’s body position and condition clearly

indicated that, although he had suffered a brutal fall, he had survived

his accident – albeit for a short period of time. Regardless of all

this, there is another strong indication that the fall did not

originate here: When I mentioned the limestone "sidewalks" of the

Yellow Band, I was not exaggerating. One would have to try quite hard

to fall out of the Yellow Band at this point. A normal slip or fall

would land one on his or her butt, and gravity and friction would do

the rest of the stopping naturally. Climbers of Mallory and Irvine’s

caliber simply would not have fallen here, let alone have a fall that

would get out of control. Clearly, the fall did not originate from the

ice axe site; there must be another explanation.

But… enough historical surmising. Storm clouds were encroaching and a

light snow had begun to fall; it was time to begin the descent back to

Camp VI. A final scour of the slabs revealed nothing more of

significance, and I began the descent through the Yellow Band. Keeping

my eyes focused footward, I fulfilled my goal of finding 1933 Camp VI

without it finding me. Alas, honesty must again prevail: It took no

looking, no great feat of anti-tripping diligence, for this year the

camp is completely exposed, its green tent fabric flapping in the

breeze. Aaah, what a searcher I could be if I did not have a conscience!

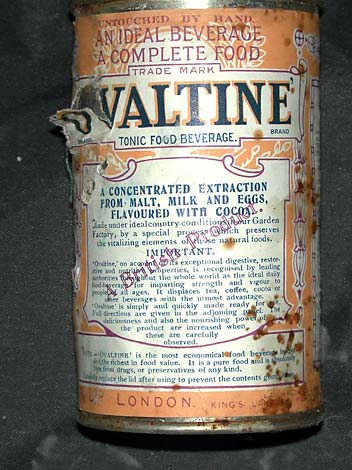

The 1933 camp amazed me immediately. The bits of paper I saw in 1999

turned out to be a virtual treasure trove of tinned goods. Carefully

chipping away the ice and rock, I slowly gained access to the portion

of the tent hiding the goods. One by one, the cans were extricated:

Nestle’s Condensed Milk, by appointment to H.M. the King; Stelna Beef;

Selected Ginger; Heinz Spaghetti; Heinz Baked Beans; Tabloid Tea;

Salmon and Shrimp Puree; several Tommy Cookers; Kendall Mint Cakes with Bruce’s endorsement from 1924; and many other fascinating tidbits from 1933. My pack was bulging, snow falling in sheets, and it had been a

long day. I decided to explore one final nook of the tent and then call

it a day. A bit of shining metal and greenish paper caught my eye.

Again, carefully chipping, I was able to remove an opened and partially

eaten box of Huntley & Palmer’s Superior Reading Biscuits. The

crackers had sat in the elements at 27,400 feet on Mount Everest for 68

years, and looked no worse for wear. I was quite curious… and more

than a bit hungry. I couldn’t resist. Perhaps it was an archaeological

faux pas. Regardless, it was great. There, in the Yellow Band in a snow

squall, I sat and ate a biscuit from 1933. It made my head spin to

think that the last person to eat out of this box may have been Wager,

Wyn-Harris, Smythe, or Shipton. Not wanting to eat more museum pieces,

I carefully packed the biscuits in their own Ziplock and pointed my

toes downhill.

So, I reckon the camp and I are now even. It may have tripped me in ’99, but I got a bite to eat out of it in ’01.

Hey Great Post! It is interesting how Everest pops out these little morsels every so often to remind us all of it’s past.

Sounded like a grand experience–by the way, what happened to the artifacts you found?

I might write a piece and link back here. Great story!

Hi Jason,

It is amazing that all these things are still lying about on the mountain – a nice, humbling reminder of the past!

As for the artifacts, all the ones we recovered in 2001 are now in Washington State. We had them on display through the Washington State Historic Society for a while, but eventually they came down.

There are plans, however, to get them up again on display – perhaps even visiting the new Bradford Washburn American Mountaineering Museum right here in Golden, Colorado.

It would be great for them to see the light of day once more!

-Jake

Hey Jake,

You know, that amazes me that no one has asked to display these items.

The Bradford-Washburn Museum would be a nice selection..

My personal belief..The Smithsonian…

Ha,ha..just a thought.

We had them on display through the Washington State Historic Society for a while, but eventually they came down.

Great piece. I admire your sense of adventure and I’m sure I would have eaten more than the biscuits. I’m curious about the spaghetti!

Dani @ ONNO Organic Clothing

Wow, I saw the picture of the old gear and I was like, what? I’m sure it was durable and all but these things have changed majorly now.