I have lots of heroes. People from various parts of my personal history, and those who I’ve interacted with only through the pages of history or media. I’ve been fortunate, though, to have worked closely with one of my childhood heroes, a figure who inspired me not only to climb, but to think more deeply about climbing that the simple act itself, and apply the lessons learned on a mountain to one’s life, and vice versa.

Today, that man – Tom Hornbein – turns 88 years young. If you’ve had the pleasure of meeting him, you know that Tom is one of those rarest of humans for whom humility is fundamental, foundational, even while success piled up throughout his long life. For Tom, climbing was and is a parable of life, and the need to embrace risk throughout our short time here. He’s done that in spades, from the West Ridge of Everest to Masherbrum, first ascents throughout Colorado and Washington to his long career in anesthesiology.

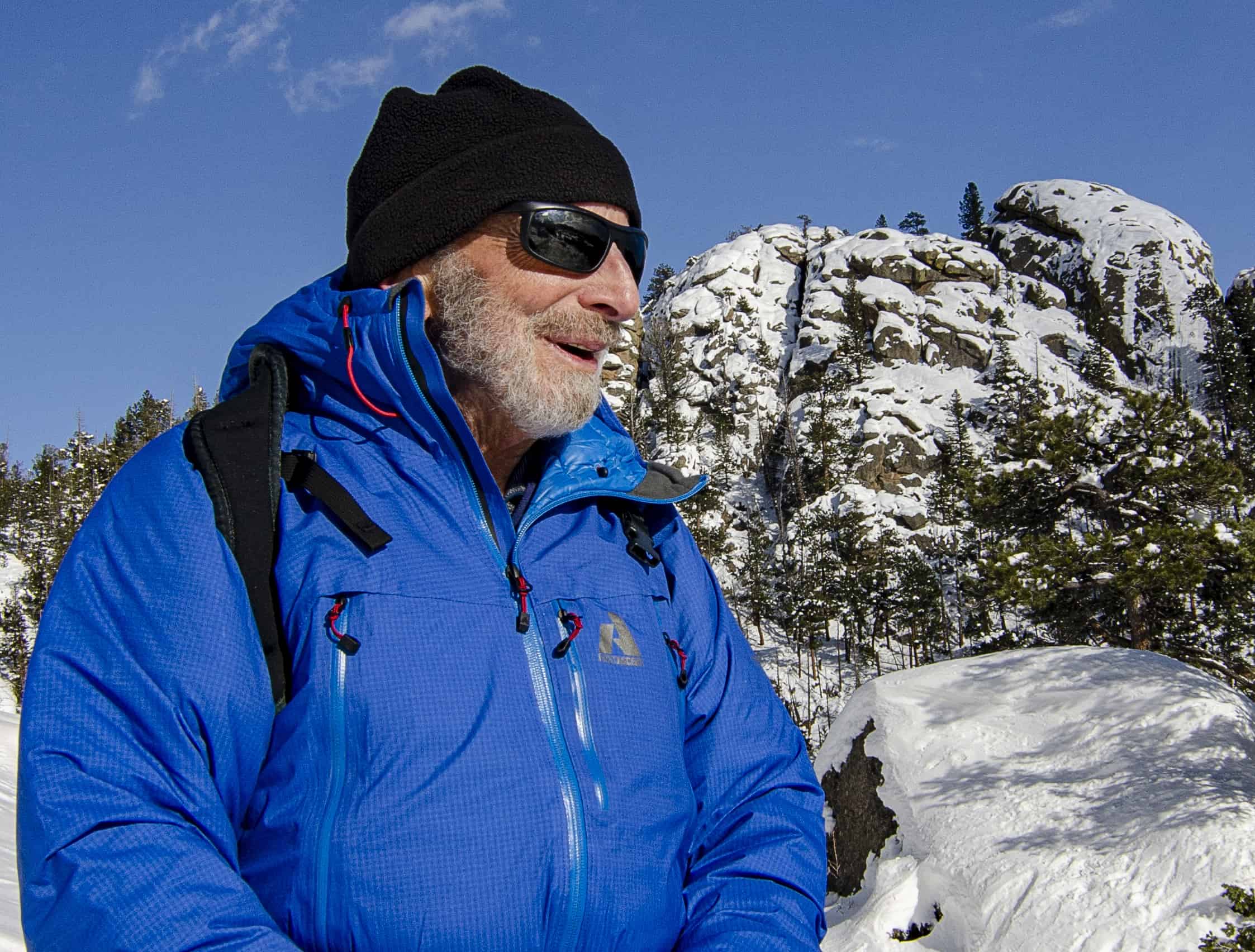

I can’t really begin to describe what a special individual Tom is, but perhaps some of his writing from his book, Everest: The West Ridge, says it better than I. And, if you're interested, see Tom in 2013 hiking near his home in Estes Park for the opener to our film, High and Hallowed: Everest 1963; it’s available on Vimeo and Amazon Prime Video.

Like pain, a mountain can be a subjective sensation; for all its solidity and fixity of form, it is more than what one sees. It is awe, pleasure, respect, love, fear, and much, much more. It is an ever-changing, maturing feeling. Over the weeks since we had first stood on the Shoulder to see the black rock of the last four thousand feet, my feelings toward the climb had steadily ripened. That rock couldn’t be divorced from the summit to which it led. Yet each time we looked, the slope seemed a few degrees gentler, the vertical distance not quite so unreasonable. After all, we had climbed steeper faces and longer distances, and on more rotten rock. But all together? And, above 27,000 feet instead of half that high? However, you can’t see altitude. Might as well ignore it. We chose not to dwell on problems like what happens if you run out of oxygen below the summit. And what it’s like to climb on rotten rock at 27,000 feet, ballasted by a forty pound pack.

Everest came down off Everest. It became, in a climbing sense, just another mountain to be approached and attempted within the context of our past experience in the Rockies, Tetons, or on Mount Rainier. Not quite, really. But much of the battle lay inside. That battle was nearly won.

I looked out beyond the Great Couloir to the step where Mallory and Irvine were last seen. So near the Everest of my boyhood, I felt uneasy, as if I were trespassing on hallowed ground. I looked on the same North Face at which they had looked forty years before; I felt what they must have felt. The past was part of the rightness of our route.

Beyond the remains of the Rongbuk Monastery were the barren hills of Tibet, a strange land of strange people, living beneath the highest mountain on earth – did they know it? What difference did it make to them? I thought of home. It would be night there, everyone asleep. Can Gene feel my thoughts coming home? I took my photo album from my shirt pocket, and looked at the portraits inside. Tears came. Sheer, happy loneliness, the feeling of being nearly finished with the task I had set myself. It wouldn’t be long now.

Completely alone. Range on range hazed westward. Beneath me, clouds drifted over the Lho La, chasing their shadows across the flat of the Rongbuk Glacier. I remembered afternoons of my childhood when I watched the changing shapes of clouds against a deep blue sky, seeing elephants and horses and soft mountains. On this lonely ridge I was part of all I saw, a single, feeble heartbeat in the span of time and space about me.